Andrade Memorial Boardwalk nixed as possible site for slave monument

Advocates for placing a memorial to the history of Bristol's involvement in the slave trade made it clear that their proposal of the boardwalk site was a mistake and that it would not be the site they propose moving forward.

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Andrade Memorial Boardwalk nixed as possible site for slave monument

Advocates for the placement of a marker acknowledging and informing people about the dark history of Bristol’s involvement with the transatlantic slave trade were forced to regroup last Wednesday evening after their initial request to the Bristol Town Council for support of the project hit an abrupt stopping point.

The merits of the proposal itself were recognized by many who spoke, and only faced sparse criticism. Rather, it was the initially-proposed location for Bristol’s port marker — in the same vicinity as the Michael Andrade memorial boardwalk that was dedicated in 2019 to the late Army veteran who died while serving in Iraq in 2003 — that drew over an hour of blowback from members of the Town Council and public alike.

“It's not the proposal that I'm frustrated with because there's a lot of value here,” Town Council President Nathan Calouro said at the onset of the presentation, previewing much of what was to come. “My frustration is tremendous on the proposed location.”

Half a dozen residents, including Fatima Andrade Milhomens, Michael Andrade’s sister, echoed that sentiment with strong rebukes during public comment while simultaneously stating that they do not want to be assumed as opponents of the port marker project in general.

“I think it’s unfair that you assume we’re all here against your project. We are not. People may feel differently about it, but I personally am not against your project. I am against the way it was proposed and where you would like to place it,” Milhomens said, later adding that she believed there were many other spots in Bristol that could serve as a proper location. “[The proposed location] is a memorial. It is a place where I go to remember him, just like many people in Bristol.”

A quick step back

Port marker advocates, throughout the presentation and public comment period following it, made it very clear that their proposal of the boardwalk site was a mistake and that it would not be the site they propose moving forward.

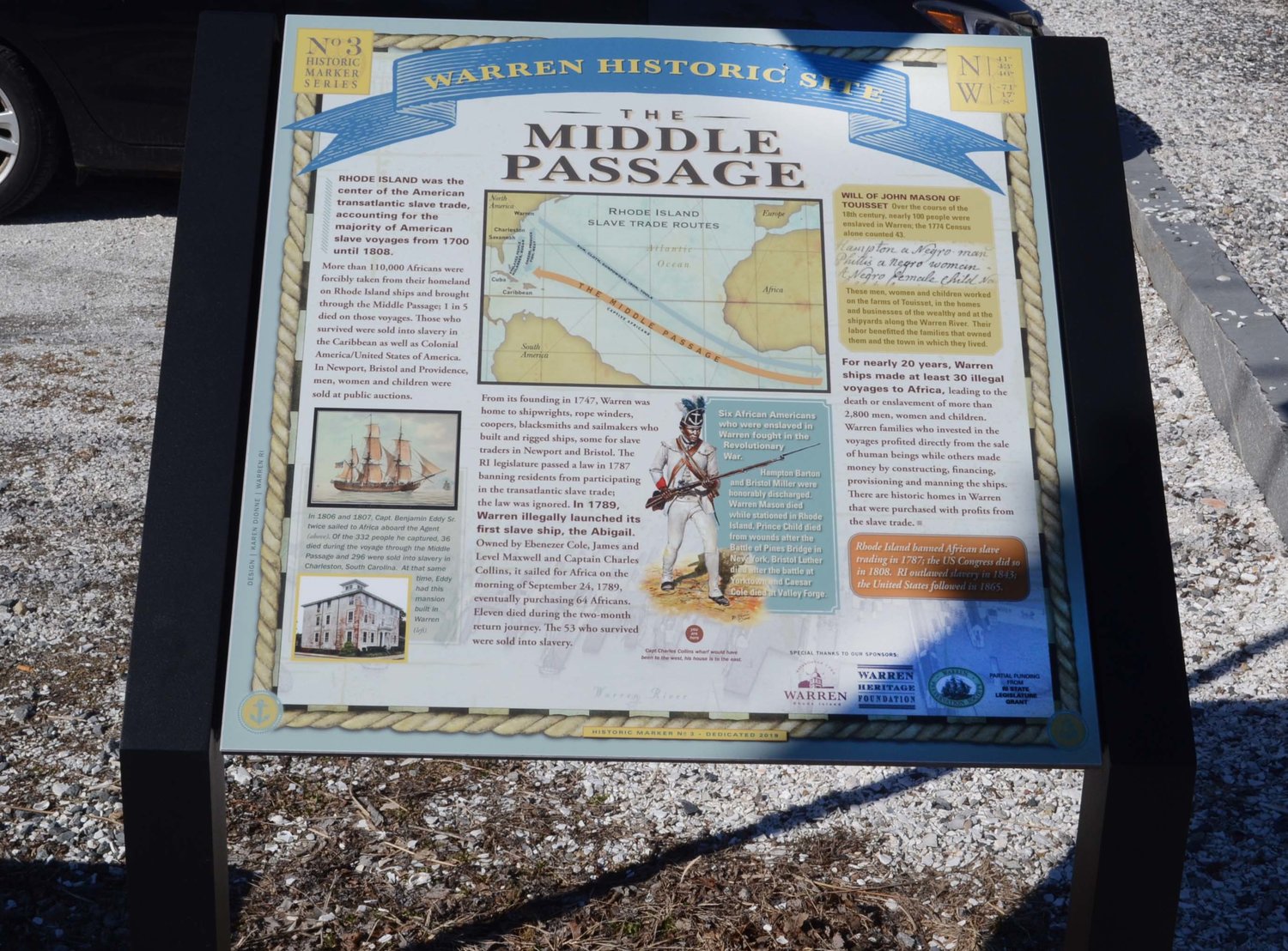

“It was very presumptuous of us to propose that site,” said Stephan Brigidi, a member of the Bristol chapter of the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project (MPCPMP), a nonprofit organization begun in 2011 with the mission to “honor the two million captive Africans who perished during the transatlantic crossing known as the Middle Passage and the ten million who survived to build the Americas.” Bristol would join 55 other such projects spanning from Texas all the way up the coast to New Hampshire.

“If at any point we thought that would be offensive, we never would have brought it further,” Brigidi continued, after apologizing to Milhomens and those who came in support of Michael Andrade and his family. “That was a mistake.”

A history that must be addressed

Dr. Catherine Zipf, Executive Director of the Bristol Historical Society and a leader on the Bristol MPCPMP, began her presentation by unfurling a 55-foot-long timeline that outlined all the known enslaved African and indigenous people that were trafficked throughout Bristol from 1680 up to when the transatlantic slave trade was finally outlawed in 1808, despite Rhode Island banning the slave trade in 1787.

According to the historical society’s research, approximately 11,000 enslaved people came to America via Bristol in that time period, although only a fraction of those remained in Bristol once they arrived. Slaveholders in Bristol were numerous, including Nathaniel Byfield and Nathan Hayman, two of the original merchants to purchase the land that would become Bristol and who became known as founders of the town.

Much more well-known, the DeWolf family bears the reputation of being most notorious slave trading family in North American history, financing 88 slave voyages between 1784 and 1807.

Many of Bristol’s most well-known locations, including DeWolf Tavern, Linden Place, Coggeshell Farm, and the very building that houses the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society, were either built utilizing slave labor, were built with funds generated by the slave trade, were built with African stones, or participated directly in the slave industry. Although not unique to Bristol, the town also relied on slave-driven industries such as Southern cotton production to bolster its economy.

The importance of a monument that more deeply approaches and engages with this topic, she said, was in part due to her belief that this history has not been properly addressed or put forth into the public consciousness.

“Is the history out there? It’s really not,” she said. “The story we have been telling is grossly incomplete…This is very hard history. We found Bristol was extremely complicit with the slave trade and in other ways.”

But more important, Zipf said, was that this project pay tribute to those thousands of enslaved people who, literally, helped build and sustain the town while forced into a life of terror and servitude.

“This is not about white people,” she said. “Anybody who is looking at this marker and seeing all of those names on the timeline as being owned by white people, that is wrong. This marker is about honoring the African and Indigenous people who were enslaved in this town in its early history and who built this town. It is not about the owners…it is about the enslaved and bringing that history to light, and bringing those people to light.”

A descendant’s dissension

Isaac Gilliard, who chairs the Bristol-based Descendant Voices in Action advocacy group, was one of the only people of color to speak during the prolonged discussion regarding the port marker.

He responded to a number of critiques brought up by members of the public, including those who pointed out that two markers referencing Bristol’s role in the slave trade already exist — one near the DeWolf Tavern on Thames Street and one recently installed outside of Linden Place.

“There's already a thought that we are doing this to make people feel bad, but we're not. We're doing this so we can talk about ourselves and we can make note of ourselves,” he said. “The markers you're talking about were done by people who were well-meaning but do not represent us.”

Gilliard said in a previous interview and in a letter to the editor that he felt the port marker group was not seriously listening to concerns or input of actual descendants of slavery, which forced him to withdraw from participating in that group. The debacle that ensued last week over the choice of location for the monument, he said, only made him more wary of the process thus far.

“The problem is that now you've put this in a bad light. Again, this is why African American people and indigenous people do not want to get involved. This is why our story is not being told. Because we pull back every single time something like this starts because it gets off to a bad start,” he said during public comment. “I agree that we’re not ready to ask for anything because we have not done the work. It’s not done…For me, this has been incredibly disappointing.

An ongoing process

The Town Council ultimately did not take any action on the matter, instead opting to table further discussion and allow the MPCPMP to come back with a new proposal that includes a new proposed location for the memorial.

Zipf said throughout the meeting that she welcomes the kind of widespread and heated discussions that have been generated by this project proposal, and that she is looking to schedule a public meeting with anyone who wants to join to better formulate the proposal going forward.

“There's no timeline. There's no pressure. We move forward as the community needs to go forward and we go backwards as the community needs to go backward, like we're doing right now,” she said. “Honestly, I expect controversy and I expect mess.”