Living by the sword in Westport

Veteran fishermen recount Westport’s glory days in the swordfishing business

Long back before everyone had a computer in their pocket or even a TV at home, Westport Point was the place to be.

Crowds would often gather at Lees Wharf to watch the boats come in, and one …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Living by the sword in Westport

Veteran fishermen recount Westport’s glory days in the swordfishing business

Long back before everyone had a computer in their pocket or even a TV at home, Westport Point was the place to be.

Crowds would often gather at Lees Wharf to watch the boats come in, and one never knew what was going to be aboard Quest, Side Show, Bycracky, Bugsie and the many other boats that fished out of Westport. But from the mid-40s through about the mid-1980s, there was a good bet the catch was swordfish brought in from the Vineyard, Nomans and points east.

“You gotta realize, this was 1945, 1944,” remembers Richie Earle, one of the last of Westport’s old time swordfishermen. “It was something to do. It was exciting.”

Nearly 40 years after Westport’s historic swordfish fishery petered out, a handful of fishermen who were at the center of the rush here brought their stories to the Westport Grange earlier this month, at the invitation of the Westport Historical Society.

Though their work was often tedious, always dangerous and hard as anything they’d done, they loved the work, the camaraderie and the rewards.

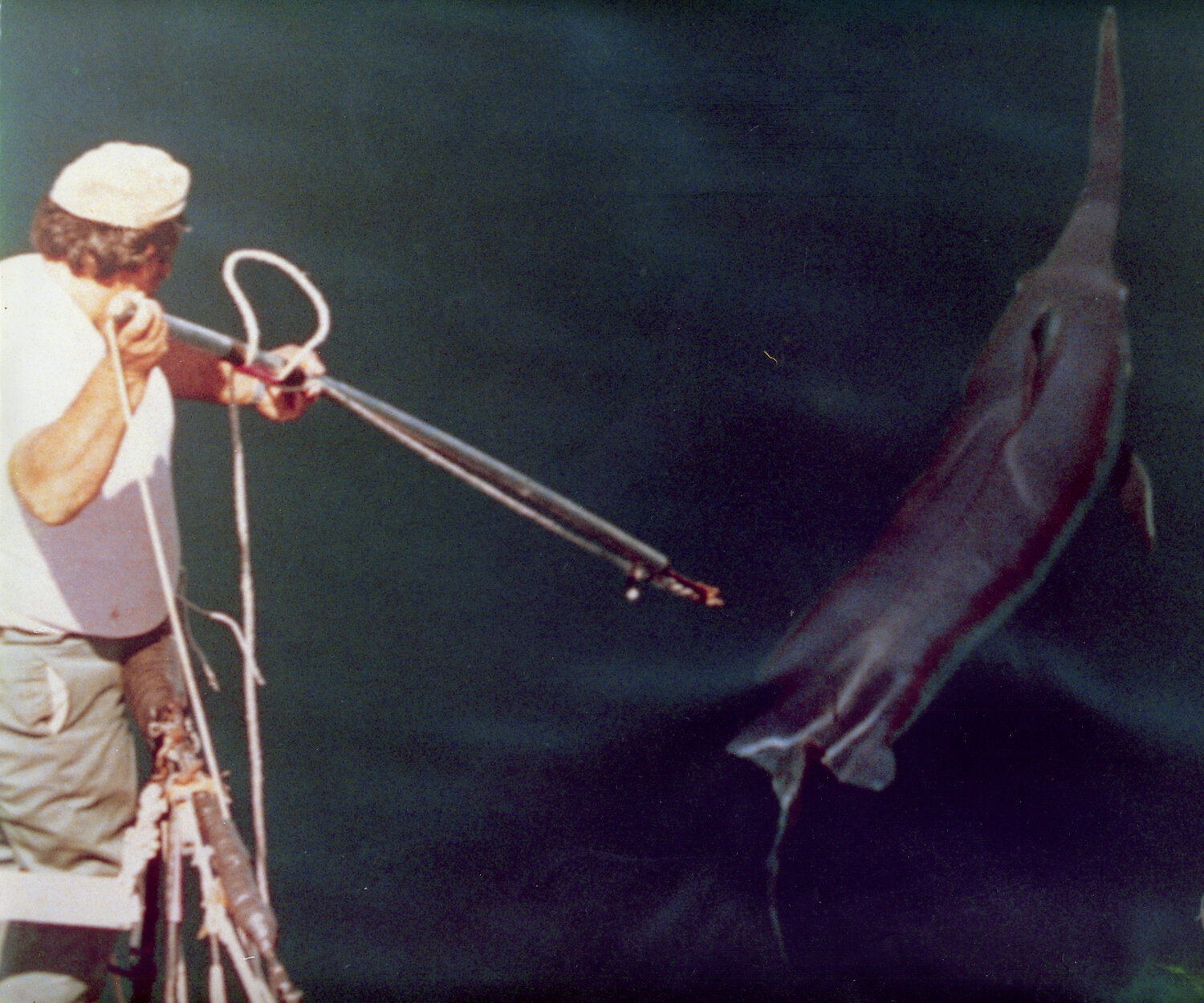

“It could be pretty hectic,” recalled Grant Moore, a striker whose job was to harpoon swordfish once they’d been spotted on the surface, usually with the aid of a watchful spotter pilot flying hundreds of feet above. “But ... it was a passion. It wasn’t about going out and making a living. It was a passion; it was trying to figure out how to do it better.”

An evolution of boats

Swordfishing existed in Westport well before its 1970s-80s heyday and there are photos of small craft rigged to catch the fish, which spend most of their lives at depth and only surface for a short period each day.

In the early days, fishermen used boats ill-equipped for the task — one photo from about Westport taken 1920 shows a small catboat, mast removed and motor added, with a striker in a small handmade pulpit off the bow. But as lobstermen, rod and reel boats and others joined the fishery, techniques and equipment evolved. Pulpits got longer, spotting masts got taller, as much as 65 feet or higher, and spotter pilots were hired to direct boats to surfaced fish. The old wooden harpoons were replaced with aluminum, and communication got better.

In the 1950s, the fish provided extra money for captains, mostly of lobster boats. But by the 1970s, due to improvements in technology, there was big money to be made in what was then a sustainable fishery.

By the time Vietnam veteran pilot Paul Brayton got involved, it had become big business and the cost of hiring a pilot was worth it for many captains.

Brayton, like other pilots who worked with boats from Little Compton to New Bedford, often spent many hours in the air, landing on the Vineyard or New Bedford to refuel as he searched for the elusive fish and kept in touch with boats via radio, Loran-C and radar. The boats would stay out for many days at a time, fishing as much as 200 miles offshore.

“Just imagine what it was like sitting in this chair,” said Brayton, referring to a photo of him in the pilot’s seat. “You couldn’t swing your legs out, you couldn’t stand up, the windows were open, it was windy, and you had to look all the time and keep flying. There were 15 other guys out there doing the same thing. It was a lot.”

When a fish was found, it was a scramble to get to it as soon as possible and the pilots would circle overhead, giving boats a visual on where they needed to go once they were close. Aboard the vessels, all got ready ... lines and floats were rigged, harpoons were prepared and strikers got ready to try to snag one.

There was danger everywhere, and Moore said there was always a chance that strikers who stuck a fish would be injured by the non-business end of the harpoon as the fish was brought up alongside the boat — that handle could end up in one’s gut if the boat was rocking and the fish was hard up against it. Other dangers lurked — one local captain struck in a head by a weight managed to bring his vessel back to Westport but died a few days later.

Politics and long-liners

By the mid-1980s, the heyday Westport’s fishermen enjoyed was coming to an end.

For years, fishermen worked a section of disputed territory off the coast of New England and Canada with few problems. But a reclassification of the country’s boundary lines took a large portion of the fertile Georges Bank grounds from US-based fishermen, seriously reducing the area they could fish. At the same time, long-liner fisherman and deep-drop rod and reel anglers were entering the picture.

“If you visualize the (fishery) as kind of like a pyramid, the bottom of the pyramid are juvenile fish that start this big,” said Brayton, holding his hands a few inches apart.

“The swordfish don’t reach sexual maturity until they are 100, 125 pounds. What we were taking was the very top of the pyramid, and you could lop that top off every year and replace what you had taken off (the next year). It was a sustainable fishery.”

“But when the long liners started taking small fish, 60 or 80 pounds, that had never reached sexual maturity, the whole pyramid shrunk. There’s still big fish, but it’s not the same volume and it’s not the same fishery.”

“Everything’s changed,” said Mills. “The water has changed, where the bait is has changed. NOAA says the resource has been rebuilt. I would question that.”

But “I feel very fortunate to have been able to be part of this and see this and experience it firsthand, because there was nothing like it. I can’t explain it. It was magical.”