Crisis management: Police are using new staff, training and tactics to confront the mental health crisis

One day last year, a woman in the East Bay area dialed 911 to get help for her daughter, who was in the middle of an emotional meltdown. Police officers on duty, who had responded to similar calls …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Crisis management: Police are using new staff, training and tactics to confront the mental health crisis

One day last year, a woman in the East Bay area dialed 911 to get help for her daughter, who was in the middle of an emotional meltdown. Police officers on duty, who had responded to similar calls from the family in the past, knew the girl suffered from a mental illness that caused frightening and sometimes violent outbursts. This time, she had engaged in cutting, a type of self-injury that experts say affects many troubled adolescents – particularly girls – and is usually a symptom of extreme emotional distress.

Rescue personnel who responded to the call transported the girl to the hospital. Two police officers were involved throughout the crisis, even after the EMTs left, serving as a reassuring presence to the girl and her family. The mom later contacted the department to express her gratitude. She specifically mentioned the police officers’ empathy, which she said helped make a horrific situation a bit more bearable.

Empathy may not be the first word that comes to mind when people imagine a police officer at their door, particularly when national news stories focusing on violent and sometimes deadly interactions involving police are so common. Those stories can overshadow the work of local law enforcement agencies, such as the three featured in this article, that are quietly transitioning to an approach characterized by restraint and compassion when dealing with troubled individuals.

These efforts, which have been evolving for over a decade, have taken on new relevance in the past two years as pandemic-related mental health issues have escalated dramatically.

The pandemic was like ‘a bomb’

Tiverton Police Chief Patrick Jones said the arrival of COVID-19 in 2020 had the impact of “a bomb” on the community’s overall mental health and sense of well-being. From his perspective, the lockdowns and other restrictions put in place two years ago supercharged everything.

“Imagine a person who was already lonely and depressed who suddenly can’t see their family, can’t see co-workers, can’t enjoy the holidays. Businesses and schools were closing, people were getting laid off. All of these added stressors were placed on folks across the country during the pandemic, and we saw it in our community,” the chief said.

Even pre-pandemic, he said, mental health issues – especially those related to isolation and depression – were a universal challenge. He recalled reading an article in 2018, right about the time he was appointed chief, that described how the former British prime minister had created a cabinet level position for a new “Minister of Loneliness,” a person in charge of addressing what was considered a serious public health concern in that country.

The chief could relate; while his officers dealt with a wide variety of complicated issues relating to community members’ mental health, loneliness and a sense of disconnectedness seemed to be at the root of many of them.

Tiverton launching a new division

Jones has been with the Tiverton Police Department for 32 years – long enough to remember a time when a deeper sense of trust existed between citizens and police. One of his goals for his department is to get that connection back.

“When I first got on the job, and I know many of the older police officers agree, folks knew all the police officers in the community, they knew where they lived and who they were. We want to get back to that … give people opportunities to meet officers, have normal conversations, have a c

up of coffee together and share a joke … We don’t want it to be where the only time they meet a police officer is on the side of the road, wh

en getting stopped, or if they have to call them when something has gone wrong.”

For the past four years, the department has focused heavily on community policing. “It started out small,” he said, “and now it has created a life of its own.” He believes programs such as “Coffee with a Cop” and annual public safety days go a long way in building trust between the community and police. With that trust will hopefully come an increased willingness for some to reach out for help, particularly in situations where a reluctance to talk openly about one’s personal mental health struggles or those of their loved ones is still the norm.

A priority for Jones in recent months has been his plan to create two new divisions within his department, one focusing on community outreach and the other on community mental health needs. The two programs, in his view, dovetail with each other in terms of overall benefits to the community.

Federal money for new programs

Last year Chief Jones applied for a $250,000, three-year grant issued through the United States Department of Justice COPS program. The grant was approved late last year and formally accepted by the town council in January. He plans to promote two officers who will be responsible for the newly established divisions. The COPS grant dollars will partially cover the costs of hiring their replacements.

During a Tiverton Town Council meeting to consider formal acceptance of the grant, council members wrestled with the decision, because an investment of municipal dollars is required to partially fund the new programs. The debate centered on whether the added financial burden to the town would be justified by perceived public benefits.

Councilor Deborah Janick echoed the sentiments voiced by other councilors during the meeting when she said, “We can’t say, ‘we can’t afford it.’ We need to find the funds for this … The COVID pandemic has brought out the worst in people. Mental health issues relating to drugs and alcohol are skyrocketing. It’s happening all over the country, all over the world. There is a lot of violence and much of it is related to mental health and poly-substance abuse.”

The mental health crisis was a common theme throughout the discussion and seemed to influence the final decision of the councilors, who voted unanimously to formally accept the grant.

The COPS grant provides funding for a three-year period; in the fourth year, the guidelines require the town to fully absorb the cost of the two new officers. What will the department look like after that?

“We can’t foresee where will be in 2026 or 2027,” Chief Jones said, “but I’d like to think these officers will be absorbed into the department.” He said the two new divisions will be fundamental components, just as the detective and uniform division are now. “It is fully my intention,” he said, “that community policing and mental health will be foundational divisions of the police department well into the future.”

Portsmouth – A team approach

Portsmouth Police Chief Brian Peters (shown at right), who has been in law enforcement for 24 years, has led the Portsmouth Police Department for just over two-and-a-half years. According to department records, mental health calls have increased 200% in the past decade — from 116 cases in 2012, to 173 in 2017, to 349 in 2021.

Three years ago, police in Portsmouth, Middletown and Newport partnered with Newport Mental Health to participate in a Mobile Crisis Program that connects a licensed clinical social

worker to first responders. Funding came from federal grant dollars received by the state and distributed to municipalities for the purpose of creating opioid crisis and substance use response programs.

Chief Peters said the social worker is based in Middletown and can assist with mental health emergencies on an on-call basis. “I definitely think it’s beneficial having them onboard,” he said.

Grant funding for the Mobile Crisis Program was set to expire after two years; however, the program will continue, said Jamie Lehane, president and CEO of Newport Mental Health, as his agency was able to procure additional state and federal funds to sustain it.

Lehane said when a 911 call related to a mental health or substance use issue is received, the dispatcher will follow usual protocols and then, if appropriate, reach out to the social worker, who will travel to the scene to work directly with first responders.

“We have a very good working relationship with our public safety departments,” Lehane said. “If it is not a dangerous situation – most of the time it is not a criminal matter – and assuming it is a safe environment, the police will usually standby or leave us with the EMTs, and our clinicians will do an assessment and try to de-escalate the situation. They will assess whether the individual is a danger to themselves or others and determine whether there is a need for transport to the emergency room.”

Mental health first aid training

Within Portsmouth PD’s ranks is an officer who has been trained as a Mental Health First Aid instructor and is certified to train other first responders. Peters said the training gives officers a different perspective in their approach to mental health emergencies, with the focus always on de-escalating a potential crisis rather than escalating it.

“We continuously look for ways to make sure nobody gets hurt when an individual becomes aggressive,” said Peters.

One new initiative is use of a BolaWrap, a remote device that releases a Kevlar cord to restrain individuals without injuring them. Newport Mental Health provided input on the device and helped the department form a policy for its use. The device was introduced fairly recently and has not yet been used except for training purposes; but Peters said it represents an additional tool for the department that allows first responders to avoid the need for an escalating use of force.

Support for the officers

Peer support is another area that has gotten increased emphasis in first responder work environments, including Portsmouth’s.

“We have an officer trained in peer support,” Peters said, “so if an officer has issues, there is an individual they can reach out to without the officer having to go through their supervisor. That individual will put them in touch with appropriate resources.

The department has also entered into an agreement with a counseling service in Fall River that operates a peer support group. “It’s a lot easier for officers who are having issues to speak and work these problems out with their peers who are experiencing and seeing the same things as them, rather than just seeing a licensed professional,” Peters said. “This is another way for them to deal with it.”

Bristol – Safe space and social training

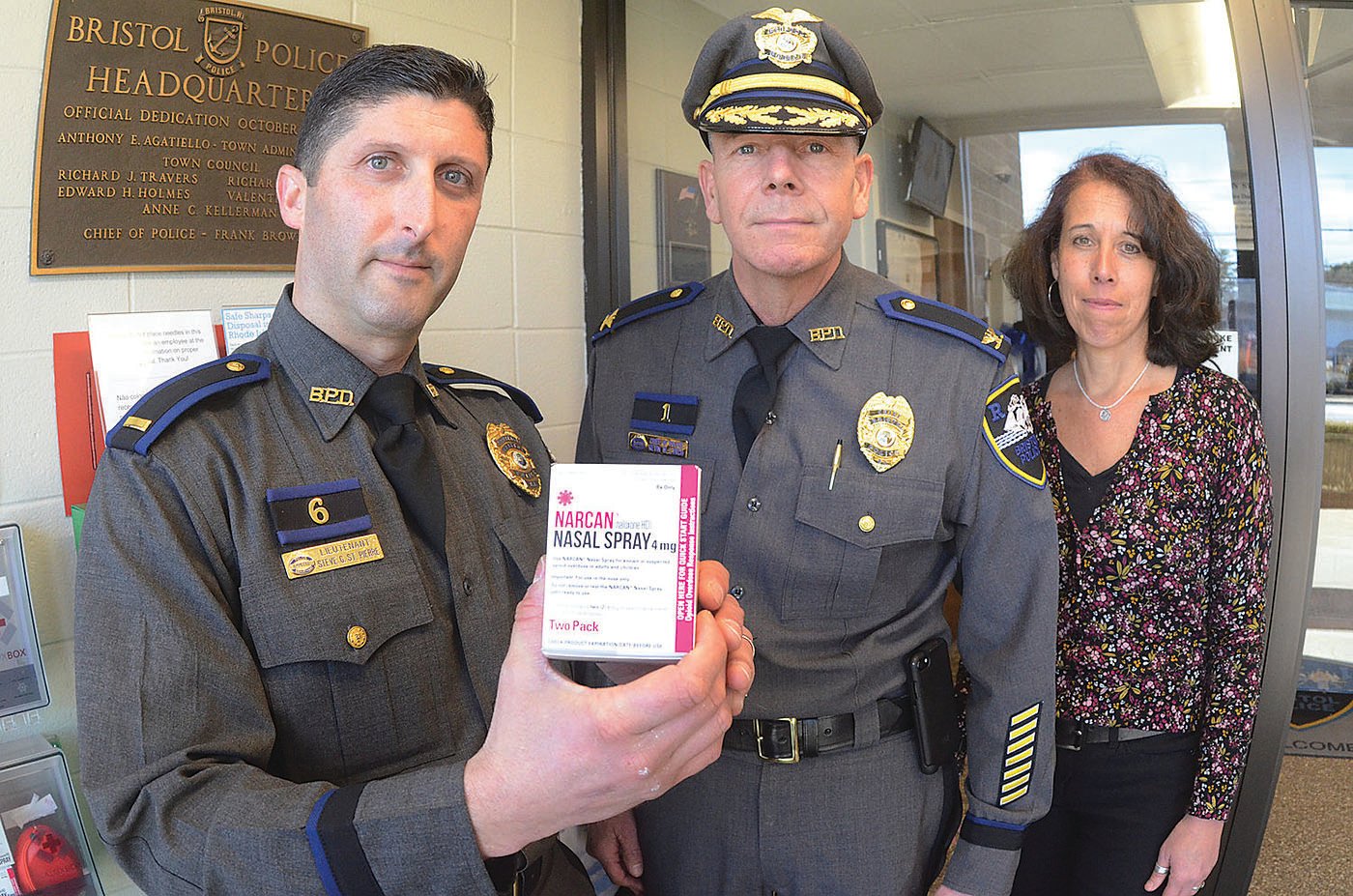

Lieutenant Steven St. Pierre is approaching 20 years in law enforcement, all with the Bristol Police Department. He is the department’s Mental Health Coordinator, a title he prefers to downplay. He seems perfect for the role, based on his depth of knowledge and strong support of the mental health initiatives undertaken by the department under the direction of Chief Kevin Lynch.

“Our agency, under the chief, takes more of a medical model when it comes to social issues, versus a law enforcement model,” said St. Pierre (shown below holding a Narcan dosage when Bristol created the first 24/7 Safe Station within a Rhode Island police station). “We view community mental health very seriously.”

He is proud that the Bristol PD was the first police department in Rhode Island to create a Safe Station – a space within the police building, open 24/7 for walk-ins, that steers individuals

with drug addictions to appropriate services in their community.

He said Chief Lynch launched the program after collaborating with Providence EMS Chief Zachariah Kenyon, who was instrumental in establishing the Safe Station program in the city’s fire stations in 2018.

“Providence started the program to help address the opioid epidemic,” St. Pierre said. If an individual did not want to go to a treatment program, or didn’t know about the programs, they could go to their local fire station and someone there would give them a referral for local treatment. If they need Narcan [an emergency treatment for an overdose] they could get it, and they would have a safe space to talk.

Bristol PD has partnered with Rhode Island’s Health Equity Zone (HEZ) and the East Bay Community Action Program (EBCAP), which connect those in crisis to treatment support and services. If a troubled individual walks into the Safe Station needing help, a recovery coach connected to EBCAP is notified immediately and will meet the person on or off-site.

A community of support

BH Link is another community partner that St. Pierre described as an excellent resource for his department. The agency, based in East Providence, offers crisis intervention services and connects people to ongoing treatment and care.

St. Pierre said Bristol officers will also reach out to community partners whenever practical when assisting an individual experiencing a mental health crisis.

“We go there with the intention of determining what services the individual needs and how we can get them aligned with those services,” he said. “That may require hospital evaluation, supplemented by a mental health evaluation.”

In these cases, he said the individual will typically be transported by emergency rescue personnel. “In a few cases, the police can do it,” he said. “But we try to avoid that as much as possible. It can make the person feel like they’ve done something wrong, or that they are in custody. We want to avoid a situation that is adding stress to an individual who is already stressed.”

The department distributes community “rack” cards on every overdose call and many mental health evaluation calls. The cards list community resources, such as EBCAP, HEZ, and East Bay Center, for a wide spectrum of community needs, St. Pierre said, and helps officers direct individuals to appropriate resources. Additionally, a community NaloxBox program provides boxes containing doses of Narcan, to counteract the effects of an overdose, at community points and private businesses throughout town and in the police station.

Lessons in empathy

When dealing with mental health emergencies, St. Pierre said, officers are trained to be empathetic, to ask the right questions, and to properly evaluate what the individual’s needs are.

“I would say in 99.9 percent of the cases, it’s just linking someone with care,” he said. “Very few cases like that will ever result in any kind of law enforcement action.”

This approach, he said, prevails throughout police departments statewide.

“I don’t want to make the assertion that this happens only in Bristol, like we are the shining star,” he said. “This is the goal of Mental Health First Aid training that police officers receive at the academy. Every officer in Rhode Island participates.”

Summarizing his perspective on his department’s culture, St. Pierre said, “I know there is a lot of discourse about police not wanting to make these [mental health related] calls. I can’t speak to that; but I can tell you from what I see in their response, we have an extremely empathetic, extremely understanding, well-educated police department and rescue department … I wouldn’t have stayed here two decades if that was not the case.”