- FRIDAY, APRIL 19, 2024

Who owns the shore?

Legislators are wading into the surf, considering shoreline access vs. ownership

Every now and then, the Rhode Island General Assembly confronts a bill that is not like other bills. It is bigger, bolder, more significant in promise and impact. The “Shoreline Access” …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Who owns the shore?

Legislators are wading into the surf, considering shoreline access vs. ownership

Every now and then, the Rhode Island General Assembly confronts a bill that is not like other bills. It is bigger, bolder, more significant in promise and impact. The “Shoreline Access” bill, officially H-8055, is one of them.

Most bills solve a small problem, like clearing up red tape so military veterans can more easily access their retirement benefits. They pass easily, and sponsors get recognition for helping a few citizens.

Other bills are Quixotic, like making prostitution legal. They die in committee and their lone sponsor gets recognition for trying.

The Shoreline Access bill is neither small nor Quixotic. If passed into law, it would impact every single shoreline property owner — thousands of them, living along hundreds of coastal miles — and potentially trigger years of lawsuits, pitting residents vs. the state.

If passed into law, it would also define the undefinable — what, exactly, is “the shore” — in an effort to both protect and clarify public access rights that trace back centuries, to a time before Rhode Island even existed, before America was even a dream.

House Bill 8055 attracted dozens of co-sponsors and it dominated one night at the Rhode Island Statehouse last week, when representatives of the House Judiciary Committee listened to three hours of testimony, both for and against. It is a bill unlike other bills, and most people living in the East Bay are largely unaware it exists.

Rights to the shore

For half a century, common law has recognized that people have rights to the shore, roughly considered the area between high and low tides. This was the standard in England when colonists first began populating the shores of North America, and it was written into the first charter for the colony of Rhode Island, signed by King Charles II in 1663: “They … shall have full and free power and liberty to continue and use the trade of fishing upon the said coast.”

In 1842, the first Rhode Island Constitution expanded those shoreline rights, stating, “The people shall continue to enjoy and freely exercise all the rights of fishery, and the privileges of the shore, to which they have been heretofore entitled under the [Charter] and usages of this state.”

In 1986, new language was added to the Rhode Island Constitution, stating: “The people shall continue to enjoy and freely exercise all the rights of fishery and the privileges of the shore … including, but not limited to, fishing from the shore, the gathering of seaweed, leaving the shore to swim in the sea, and passage along the shore.”

So rights to “the shore” have been part of Rhode Island’s DNA for centuries. The problem is, no one actually defined where that shore exists. Most people could walk along a shoreline and see the difference between the sea and the manicured lawns of private property owners. But writing that description into a legal document — or a Constitution, or an arrest report, or a lawsuit — is another matter entirely.

The mean-high-tide

In 1979, six men were convicted of trespassing in a Rhode Island district court. They were part of an organization working to clean the state’s beaches and shores, and they apparently had a longstanding feud with one waterfront landowner in Westerly. They were either on or near his property when they were arrested.

They appealed their convictions, won the appeals in Superior Court, and the State of Rhode Island petitioned the case to the R.I. Supreme Court. The case culminated in July of 1982, when the court issued judgement in a landmark ruling known as “State vs. Ibbison et. al.”

The case was complex, and legal scholars will want to read it for themselves, but the big takeaway is that the court, for the first time in Rhode Island’s legal history, provided a definition of the shore. It wrote that the shore is determined by “the mean-high-tide line,” further defined as an average of all high tides over an astronomical cycle of 18.6 years.

So that has been the legal standard in Rhode Island for nearly 40 years. If you are able to study high tides in exactly the same location for nearly two decades, the demarcation between public access and private property would be the average height of those roughly 14,000 high tides.

Advocates say it sounds good, but it is entirely useless, as no one could stand on a beach and discern the average high tide over the previous 18.6 years.

The tide plus 10

Two years ago, shoreline access advocate Scott Keeley, a resident of Charlestown, went walking along the shore in front of a group of waterfront properties that had hired a security guard to keep people off their land. He defied instructions to leave the area, and he was arrested by South Kingstown police officers.

Charges were dropped the next day, but the affair brought the desired attention to an issue that had been building for years. The exploding values of real estate, in general, and waterfront real estate, in particular, have increased tensions around the issues of public access vs. private property rights. Public access advocates demand the rights deeded to them in Rhode Island’s founding documents, while multi-million-dollar landowners paying $100,000 or more in annual property taxes demand their rights to exclusive use of the waterfront, without a group of college buddies setting up a volleyball net and leaving beer cans in their back yard.

The tension found its way to the Rhode Island General Assembly, which a year ago formed a special commission to study the issues of shoreline access and report back.

Rep. Terri Cortvriend, representing Portsmouth and Middletown, was named chairwoman of the committee, which included the directors of the Coastal Resources Management Council and Save the Bay, a representative from the Marine Affairs Institute at the Roger Williams School of Law, a professor of Marine Affairs from the University of Rhode Island, a representative from the Rhode Island Realtors Association, retired Rhode Island Supreme Court Justice Francis Flaherty, and others.

The commission met for months, heard presentations from scores of experts and witnesses, researched Rhode Island case law, and received written testimony from hundreds of people (the vast majority of them from the South County region). Two weeks ago, the commission issued its final report, with one enormous recommendation — a new definition of “the shore.”

The commission uses the term “Recognizable High Tide Line” as the new standard of measurement, defined as the area of land where the most recent high tide is visible, plus another 10 feet.

The advocates

Rep. Cortvriend steered the commission that landed on this bold new definition of the public shoreline, even though she had no idea where this would lead when she started. A couple of years ago, her legislative efforts were focused on sea level rise more than anything.

But as she studied sea level rise, a new question started to become evident: “As sea level comes up the beach, who’s going to lose? Whose beach is that?” Cortvriend wondered.

Then came Covid, and shoreline access issues seemed even more relevant. With so many “take it outside” efforts happening, people began wandering the state’s shorelines more than any time in recent memory. They often wandered into gray areas, somewhere between the clear spaces of public access and the crowded developments of exclusive waterfront properties.

When the General Assembly formed the study commission last year, Cortvriend was front and center. She said not all 12 members entered the process with a shared vision of the shore, but in the end they voted unanimously in favor of their recommendations, with two exceptions. The representative from the Attorney General’s Office abstained, as there could be future lawsuits vs. the state. The representative from the association of Realtors abstained as well.

According to Cortvriend, the commission was overwhelmingly influenced by the scientists who have been studying the shore and the tide lines, who say the “mean high tide” of the past 18.6 years (the definition created by the Supreme Court in 1982) is actually underwater a majority of the time — a result of both rising seas and the incredible fluctuation of tides throughout the year.

States the commission’s report: “The mean high water line is underwater on the Rhode Island shoreline most of the day, meaning the public must wade into the ocean to legally walk along the shore at a depth that could range from inches to feet of water.”

Said Cortvriend, “The commissioners did not think that people should have to walk in the water to exercise their rights, nor did they think people should have to walk through the seaweed line to exercise their rights.”

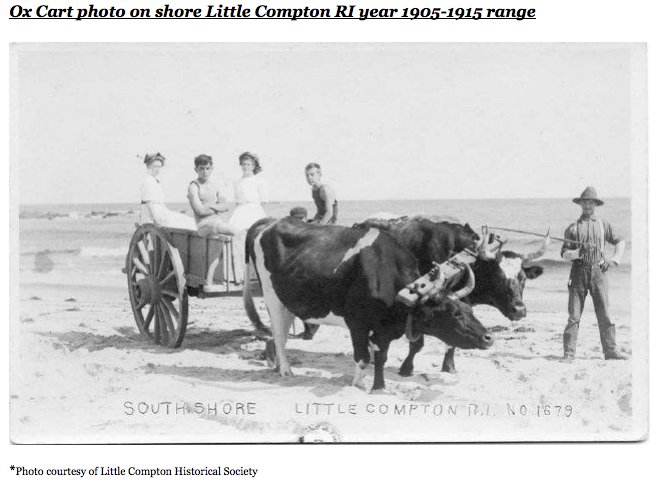

So the commission decided the public access line must be a high tide line (so the shore could be accessible at all times of day), plus another buffer for legal passage. It actually went so far back as to study the width of ox carts — once used by farmers to gather seaweed as fertilizer for the fields — with an actual ox cart preserved in a museum measuring about 8 feet wide. Using that standard, they felt that a farmer leading an ox cart would have taken up about 10 feet of space. So their suggested new standard is based loosely around the centuries-old practice of farmers gathering seaweed along the shore.

“At the end of the day, we all worked so well together, and it took a lot of talking, but we did have consensus,” Cortvriend said.

The opponents

Not everyone loves the proposed, new definition of the shore. Attorney Daniel Procaccini testified at length before the House Judiciary Committee last week. He represents a group calling itself Shoreline Taxpayers Association for Respectful Traverse, Environmental Responsibility and Safety, Inc. — STARTERS.

The group formed a year ago without publicizing its members or funders and has since hired both lobbyists and legal representatives. Interviewed a few days after his appearance at the Statehouse, Procaccini said he was recently hired by the group and does not know the full roll of members, but that his phone has been ringing a lot more lately. “In the last 24 to 48 hours, I have personally been receiving calls from landowners throughout the state who were unaware of this and its potential consequences,” he said on Friday.

Rep. Cortvriend said during an interview this week that her commission is not trying to seize private property. “We are not advocating for changing property boundaries. We are willing to accept that homeowners own to mean high tide. We accept that is a measurement that can be determined by a surveyor,” she said.

They are hoping to establish that the public has access rights that trump all private property deeds, even if the public has to cross upon what would be considered private shoreline properties to exercise those rights.

That creates a problem for Procaccini and his clients, some of whom are commercial enterprises, such as restaurants, hotels and beach clubs. He made it crystal clear to the Judiciary committee last week that passage of this bill would immediately trigger claims that the state had taken private property rights, and the thousands of waterfront owners must be compensated for their losses.

“It’s categorical. It’s like a light switch,” Procaccini said. “If this passes, and it’s adopted, it will constitute a taking, and there is a duty to pay these owners … And the calculations are large and they are complicated.”

Disappointment in the commission

Procaccini, who has authored two papers on shorelines issues, is disappointed the commission did not go further in its recommendations. While he refutes the new definition of the shore as an acceptable standard, and he also suggests it is flawed because many shores do not always have a recognizable seaweed line, he also wishes the commission had gone further to identify the acceptable uses of the public trust along the shore.

“By and large, here in Rhode Island, it seems that people are able to pass down the shore without harassments, and that issue doesn’t seem to be on people’s minds as much as what people are allowed to do on the shore,” Procaccini said. “Are they able to set down chairs and set up a volleyball net? The current bill does not do much to cure that ambiguity.”

Procaccini acknowledges that the state has every right to turn this legislation into law, setting the new definition of the shore as the recognizable seaweed line plus 10 more feet. But if it does, it will be denying property owners of one of the fundamental rights of private property — the right to exclusion.

Procaccini said that if the bill passes, the state will be taking away this fundamental private property right; property values will be impacted; tax impacts will be significant. He echoed what one private property owner said while testifying before the House committee last week.

The South County landowner told the General Assembly that he owns a small cottage on the beach. “If I don’t own down to the waterline, then why is my 754-square-foot cottage assessed at more than a million dollars?”

The Shoreline Access bill remains in the House Judiciary Committee, with interest and awareness building in anticipation of what legislators might do.

Other items that may interest you