- TUESDAY, APRIL 16, 2024

Restaurants short on staff and high on stress — Apply within

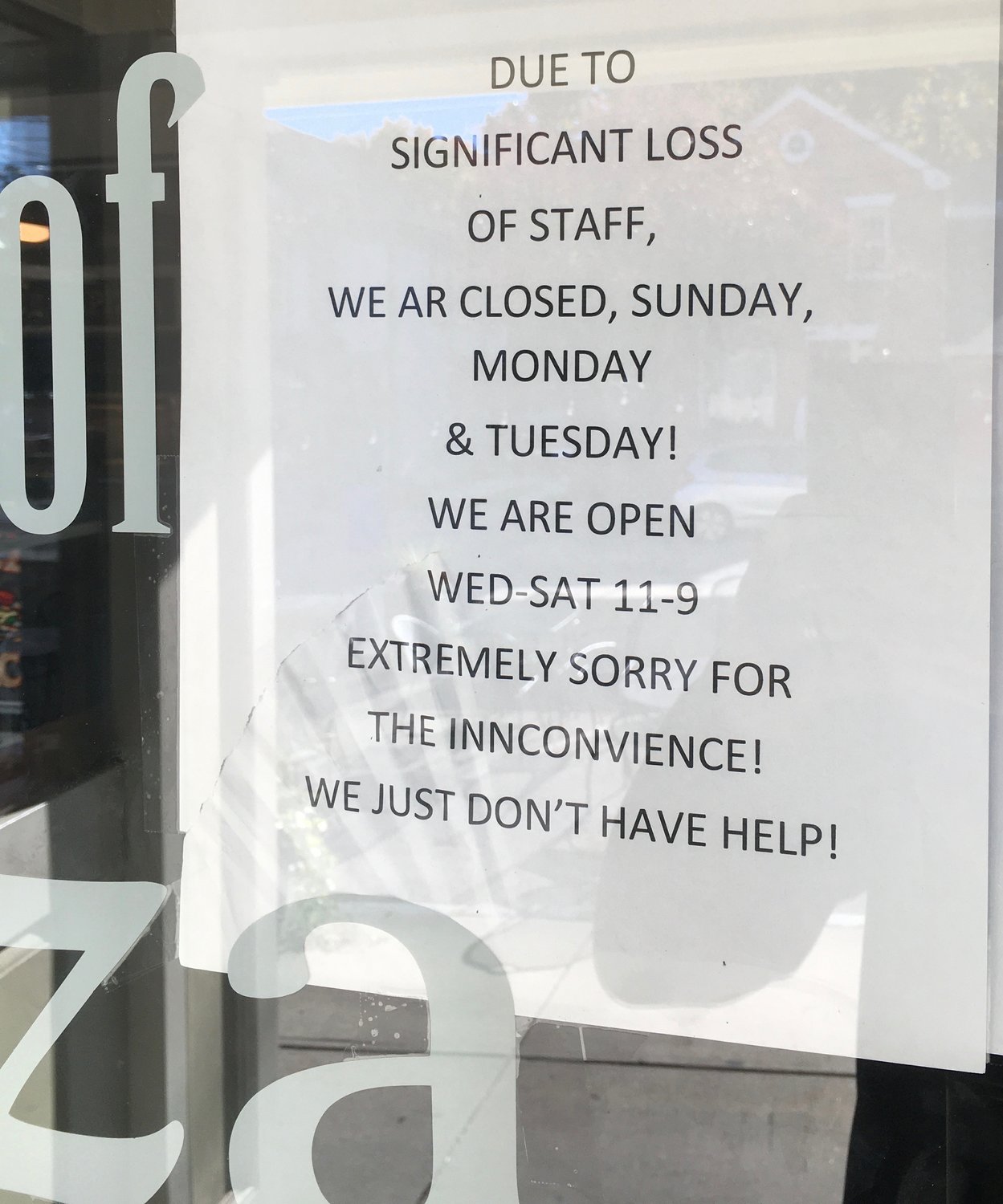

The signs are everywhere. Literally, the signs are everywhere.

“Help Wanted.”

“Now hiring.”

“Seeking: Line Cooks, Bartenders, Dishwashers.”

Almost …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Restaurants short on staff and high on stress — Apply within

Like this story and want to help us do more?

The signs are everywhere. Literally, the signs are everywhere.

“Help Wanted.”

“Now hiring.”

“Seeking: Line Cooks, Bartenders, Dishwashers.”

Almost every restaurant, everywhere, needs help. It’s not a new phenomenon. The local restaurant industry has been facing a labor shortage for months. Many survived the summer, their busiest season, through grit and perseverance — but they say it was not easy, and it was not fun.

The great irony is that business is booming for many. They report record sales, with 2021 revenues surpassing 2019, their last non-Covid year. People tired of being cooped up at home, who canceled vacations and aren’t going to shows or concerts and have disposable income, are flocking to local restaurants, enjoying a few fleeting moments of indulgence.

Yet some of those who are the backbone of the restaurant industry, the managers who struggle to keep these places thriving while the “back of the house” (everything behind those kitchen doors) is in chaos, wonder if this is a temporary crisis that will correct itself, or if it’s an inflection point for the entire industry.

Open positions, increasing wages

Ben Wachter is manager of Thames Waterside Grille, which enjoys a spectacular spot on the Bristol Harbor waterfront. He began working there at the beginning of the 2021 summer season, and the challenge has been worse than anything he’s faced in 20 years in the industry, most of it spent as an executive chef or manager.

“I had no choice, I was back in the kitchen every Friday, Saturday and Sunday, just trying to will us through the season … It was a chaotic season,” Wachter said.

Thames Waterside began the seasonal hiring process back in the spring, recruiting employees for the busy season. They placed ads on Indeed and Craigslist and got no responses. Their highest needs were then, and still are, the back-of-the-house positions, the traditionally low-wage roles in the kitchen.

When their initial ads brought no response, they tried sponsoring the ads, spending hundreds of dollars to bring more attention and elevate them to prominent spots in front of job-seekers. They still received no qualified applicants.

“I heard from a few people who worked at Dunkin’ Donuts, but it’s a whole different animal working in a kitchen like this. It’s a trade. It’s a skill. And then a lot of times I would set up an interview, and they wouldn’t show up for the interview,” Wachter said.

Next he began networking with existing employees to recruit their friends or past colleagues from other restaurants. That brought a new pressure — on wages. As staff, both new and existing, recognized the restaurant’s desperation, they realized they had the leverage.

“A job that used to pay $13 to $14 an hour as a line cook, maybe $11 to $12 an hour as a dishwasher, I’ve gone to $15 for dishwashers, and I’ve gone to $18 to $20 an hour for a line cook, in the past six months,” Wachter said.

Many times, even those pay increases weren’t enough.

“I was paying a guy $19 an hour as a line cook, and he was working 70 hours a week. Do the math. He was making more than I was, without any of the responsibility. He just had to show up to work, do the shift, and go home. Then he bartered with me to get a $2-an-hour raise. I told him I’d give him the $2, but that’s as far as I can go. Well, he took the $2 an hour, went to another job he was applying for, and they gave him $23 an hour, and promised him six days a week.” That’s when Wachter began spending three nights a week in the kitchen.

Good for business, bad for staff

The manager of The Red Dory restaurant along Main Road in Tiverton has a similar story: months of “help wanted” ads, few qualified applicants, and a chaotic summer season that never really ended.

“This summer was crazy. We were holding things together by the seams,” said Jared Marcus, who’s been the manager of the popular eatery for three years. “It’s definitely been stressful. This summer, unlike others summers, every single day was like a Saturday. We had to be fully staffed every day we were open.”

Because of staffing shortages, they couldn’t open every day, so they did the best they could from Wednesday to Sunday. Even then, they were short-handed. “As a manager, you do anything you can to help. You’re hopping behind the bar, doing a lot of food running, doing everything you can to alleviate the pressure wherever you can. It’s great for the business, but it’s stressful,” Marcus said.

Several times they had to shut the bar to food service on busy nights, doing only a service bar for the tables. Even with the reduced schedule and occasional reductions, this has been the restaurant’s best year ever. “We blew all our previous numbers out of the water,” Marcus said.

This year has also been unique because the busy summer season never really ended. “We had almost no drop-off in September,” Marcus said. “Nothing slowed down. September was almost as good as August, and then October was almost as good as September.”

The booming business has placed even more pressure on staffing, with the restaurant needing robust staffing for more days and longer hours than ever before. Even now, The Red Dory is looking for help. Marcus has been busy trying to find and train hosts, they need a bartender, and they always need help in the kitchen.

“It’s an all hands on deck situation, all the time,” he said.

No one left to work

Bristol House of Pizza has been extremely vocal about the staffing shortage. Manager and owner Greg Gatos has posted signs, left grumpy greetings on the business answering machine, and told many of his loyal customers about his simmering frustration.

He partly blames the work ethic in the young generation. “What’s happened with this generation, I don’t know if we call them millennials, is exasperating … Many of them are sensitive, they can be lazy, they have a poor work ethic, they’re selfish,” Gatos said. “I was seeing that pre-Covid, then Covid happened and it just intensified.”

Bristol House of Pizza has been in business for a couple of generations. Tula and George Gatos started it 44 years ago, and their son grew up in the business. He says he’s heartbroken by the current situation.

Pre-Covid, they employed 22 to 25 people, most working the phones, the orders and the customers. They’re down to three, plus Gatos’ niece, who helps out a few hours when she can.

“I refused to shut down,” Gatos said about the early days of the pandemic. “I wanted to provide my employees with an income. So I didn’t close … But then one by one, I started getting these little letters in the mail, from the Department of Labor and Training. Obviously everyone had become well educated about the extra $600 a week [in federal unemployment assistance]. So our staff just started dwindling. People just stopped showing up to work … Some used the excuse of ‘Covid,’ that they were scared to go to work.”

They lost about 50 percent of their employees right in the beginning of the pandemic. Many more stayed with the business into the winter, but every day was a grind. “In the beginning, it was nuts. It was like a Friday night, every single day. We needed even more employees. We needed everyone we could,” Gatos said.

Then last winter, more employees began leaving. “People just started dropping,” he said.

These days, Gatos relies on his parents — who are in their seventies and were supposed to be retired by now — to keep the place running.

“My poor parents. We had a plan for them. They were going to semi-retire … These poor bastards are working their [butts] off, harder than they’ve ever worked in their lives, and it breaks my heart. They should not be working this hard,” Gatos said. “A few Thursdays ago, I had to shut down at 8 p.m. because I was scared. I thought my mother was going to have cardiac arrest, she was working so hard. She could barely stand on her feet.”

They’ve cut back considerably, now opening only four days a week. A sign on the front door explains why — staffing. “We’re closed on Sundays. Do you know how difficult that is? To be closed on football Sundays? We’re talking a $9,000 to $12,000 loss on one day. Those other two days, it’s $18,000 to $21,000. That’s a lot of money,” Gatos said.

Gatos has never stopped looking for help, mostly so they can reopen more days. He advertises on social media, through word of mouth and through job sites. He rarely finds any decent applicants.

“We want to go back to our normal schedule,” he said. “This is a for-profit business. I’m sick of dipping into our savings. It’s getting old.”

Every year, they typically get one or two students from Roger Williams University to come work for them. This year, they have not had a single applicant.

“We’ve posted at the college. We’ve posted on social media. Instagram. Word of mouth. We’re looking everywhere,” Gatos said. “And I know we’re desperate, but we’re not going to hire just anyone. We’re a family business, we have a great reputation, we’re looking for good people.”

Like others in the industry, Gatos has increased wages — about 20 percent. Yet he’s still not seeing applicants.

Government trying to help

The challenges in the labor market are not unique to the East Bay restaurant industry. They are being felt everywhere. Just last week, the State of Rhode Island, recognizing the labor shortage across many industries, directed a pile of money toward solving the problem.

On Tuesday, Nov. 2, Gov. Dan McKee and Matthew Weldon, director of the Department of Labor and Training, announced a new “Back to Business” program, offering grants of up to $5,000 to small businesses. The funds could be used to help eligible small businesses provide “recruitment and incentive packages” to get Rhode Islanders back to work.

The state allocated $4.5 million to the program. It announced the “first-come, first-served” structure on a Tuesday. It began accepting applications two days later. In a matter of hours, the program was essentially closed, with this message posted to the application portal: “Due to an overwhelming response and high volume of funding requests received, applications submitted after 5 p.m. on Nov. 4, 2021, will continue to be accepted, but will be placed on a wait list. Please note that all applications submitted are time stamped. Grant monies are available on a first come, first served basis; however, priority will be given to employers who have not received funding through similar federal initiatives (such as Restaurant Revitalization Funds or Shuttered Venue Operators Grants) and who have fewer than fifty (50) employees.”

A new job board

Local government is trying to help as well. Chris Vitale, economic development coordinator for the Town of Bristol, is working to build a new regional job board, which will be a free service for area businesses. He’s collaborating with Mt. Hope High School marketing and design students to build a new website, for free postings of job openings, resumés and applications.

He’s trying to network with the Town of Warren, the Town of Barrington and the East Bay Chamber of Commerce to get everyone working together on the project. Vitale wants the new site functioning by the end of November.

“A lot of businesses are struggling to find workers right now,” Vitale said. “However we can help facilitate, we’re going to do whatever we can.”

Inflection point for the industry?

All three managers interviewed for this story believe this is a pivotal moment for the restaurant industry. The pandemic, economic shutdown and governmental assistance programs have brought many industry inequities to the surface.

“I don’t think this industry provides enough for back-of-the-house workers to make them want to work in it,” said Wachter, of Thames Waterside. He said restaurants are typically structured to reward executive chefs and managers, and to pay low wages to kitchen workers, including the line cooks who keep places running. Meanwhile, “front-of-the-house” employees (waitstaff and bartenders) stay motivated by the generous tips of appreciative diners.

“I don’t think that we’re coming back from this as an industry,” Wachter said. “I think that because of the low-wage, hourly positions, people are leaving the industry in hordes. I think they’re going to places like Amazon, where they can make the same $19 an hour as a driver. I just don’t feel like there’s an appeal to keep working in this business, in the back of the house, for dishwashers, line cooks … You’ve got 100-degree heat, high-stress conditions, nonstop demands. Why wouldn’t I go make $19 an hour and drive for Amazon or UPS, and have my own schedule, and my own quiet place to work on the road?”

Said Marcus at The Red Dory, “Everybody understands it’s a tough business to work in … I think a lot of people have stopped and reconsidered whether they want to work in hospitality … A lot of people have taken a look at their lives, they’ve reconsidered what they want to do, and they’ve gone in a different direction.”

Marcus is also critical of some of the government influences on their industry. He said the highly publicized Restaurant Revitalization Fund, designed to bolster restaurants that were forced to close their doors through the height of the pandemic, created great inequities. According to reports, the state distributed more than $100 million of assistance to more than 400 businesses, but that left more than 1,000 businesses with nothing. The businesses that received assistance are flush with cash — thus, able to raise wages and hire away experienced workers from their competitors.

“They gave full grants to certain places and nothing to others,” Marcus said. “There are all sorts of inequities in the restaurant industry.”

Gatos remains frustrated by the government, by young workers and by the challenges they continue to face every day.

“We’re sick and tired of being sick and tired,” he said. “There are a lot of people in this industry who are contemplating walking away.”

Other items that may interest you