In Warren, a revelatory discovery has hidden in plain sight since 1877

Unprecedented stained glass window portraying Jesus and Biblical figures as persons of color has sparked worldwide conversation

A stained glass window, installed over 145 years ago at the former St. Mark's Church in Warren, displays Jesus and Gospel figures as persons of color, sparking widespread discussion and interest in its origins and implications.

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

In Warren, a revelatory discovery has hidden in plain sight since 1877

Unprecedented stained glass window portraying Jesus and Biblical figures as persons of color has sparked worldwide conversation

At the intersection of thorny history, art, faith, and more than a little bit of luck, there stands a striking physical symbol representing all of the above in the heart of Warren’s downtown waterfront district.

A stained glass window — 12 feet in height and intricately decorated, which definitively depicts Jesus and well-known Biblical figures with dark skin tones and represents what experts call a “radical” departure from the norm, commissioned by a white woman, installed in 1877, and dedicated to two women who at one point had each wed into two of the most notorious slave profiteering families of their time — had been on display unnoticed for over 140 years.

While its discovery has been heralded by various press outlets as an historical first — perhaps the oldest known public depiction of a Black Jesus and Black Gospel figures — the wide array of art, history, and religious experts who have analyzed the window since posit that the significance of the window goes beyond that headline-grabbing surface detail.

“From my point of view now, it's not just a curious object,” said Bob Dilworth, professor emeritus and former chair of the Department of Art and Art History at URI, who led a recent discussion at Brown University regarding the window. “I think we tend to get focused on the stained glass window, but it is really about the conversation that it it generates. It has a different kind of meaning now for us as we look through the lens of our 21st century. What does that mean for us? And these are questions that I don't think can be answered neatly. You know, history is just really messy.”

The discovery

On its own, St. Mark’s Church (located at 21 Lyndon Street) already stands out among the many storied architectural buildings that pepper the surrounding blocks.

Shining brilliantly white in the cloudless sunshine of a warm April afternoon, the structure Russell Warren designed and which was built in 1830 looks much as it did nearly 200 years ago — save for its original squared parapet and bell tower, which were deconstructed some time after the Hurricane of 1938, which felled a tree that you could say miraculously spared the stained glass windows.

The tale of the church’s near demolition and revival is a story worthy of dozens of column inches on its own, but a character central to that story — the building’s current owner, Hadley Arnold — is largely responsible for this one as well.

In June of 2022, in the midst of renovating the interior of the church into a private residence and restoring the exterior to the specifications originally designed by Russell Warren, Arnold came across something she found unusual. A Harvard-trained art historian, Arnold knew she wanted to salvage the ornate stained glass windows that had long shone down colorful Biblical scenes to churchgoers. But while looking closely at one panel, she knew she needed a more scholarly opinion.

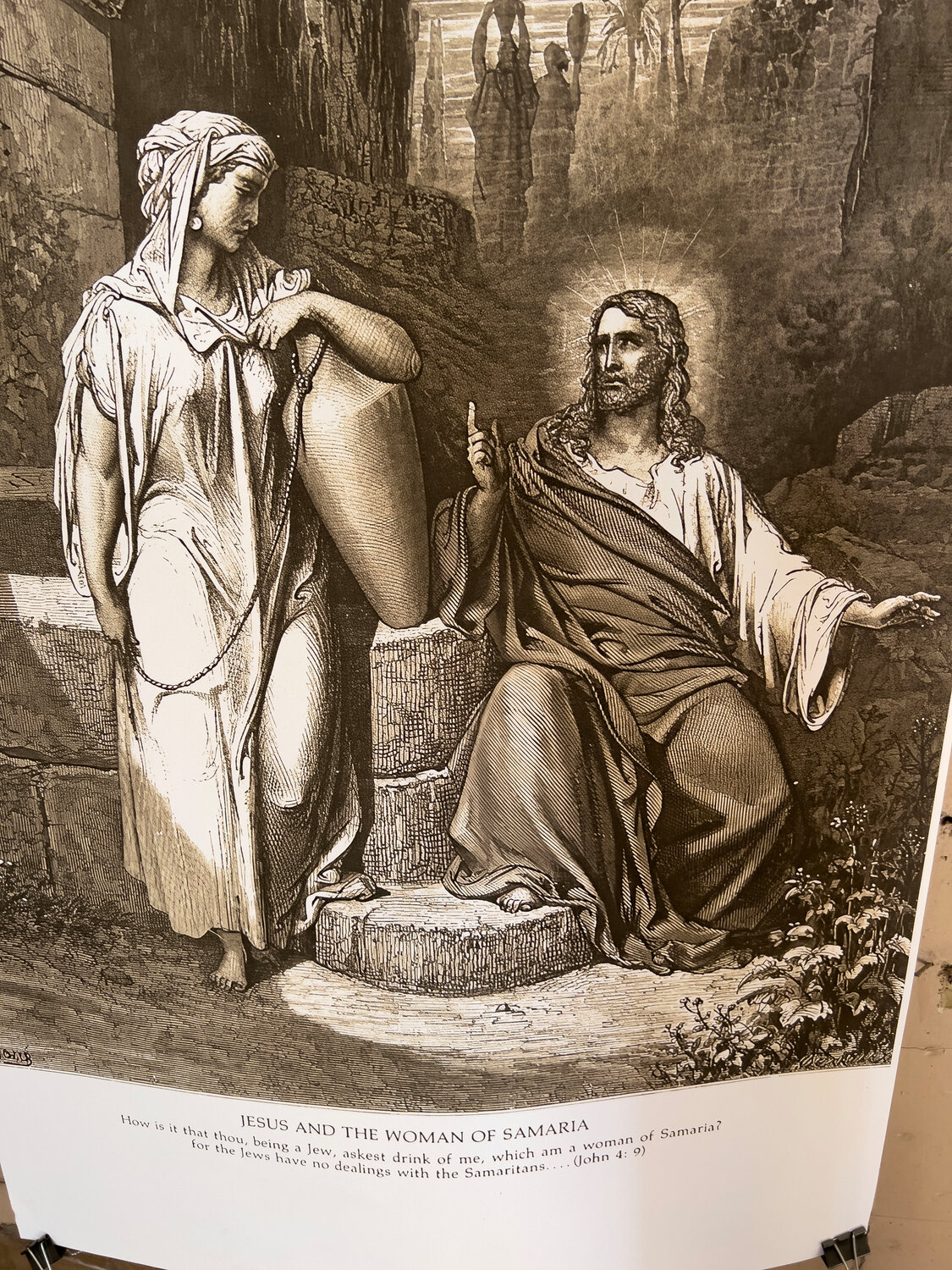

The two scenes within the glass included two well-known Biblical stories — one depicting Martha and Mary being visited by Jesus, the other a scene of Jesus conversing with a Samaritan woman at a well — but the dark skin tones of the Biblical figures depicted, she noticed, were anything but common, especially in comparison to the white skin tones of Biblical figures featured on the church’s other stained glass panels. So she called the region’s foremost stained glass expert, Dr. Virginia Raguin, who literally wrote the book on the history and significance of stained glass.

“Virginia climbed up and she said, ‘This is exactly what you think it is, and we’ve never seen anything like it,’” Arnold recalled.

Raguin, along with another expert, were able to confirm the depiction of dark skin tone was original and purposeful. But it is also not the only unique aspect seen in the window.

In the traditional telling of the story of Martha and Mary, Jesus reprimands Martha for being critical of Mary, who had been worshipping at the feet of Jesus while Martha hurried about to serve him. In the St. Mark’s depiction, Jesus sits among them, seemingly in mutual discussion. Whereas the traditional telling has the women symbolically on either side of Jesus, in the window, they are on the same side.

“That is amazingly radical,” Raguin, who earned her Ph.D. from Yale and has since retired from the College of the Holy Cross said. “I’ve never seen this anywhere else before.”

The window’s past

The discovery ignited a thirst for more knowledge about how the window came to be displayed in a Warren church amidst a fraught time period at the end of the Reconstruction Era, where freed Black slaves, white abolitionists, and everyone in between were trying to piece the country back together following the Civil War.

In the case of the window itself, the shadow of powerful families whose fortunes were built on the backs of forced labor and human trafficking also looms large and unavoidable.

The window was dedicated to Hannah Bourne Gibbs and Ruth Bourne DeWolf, two sisters born in 1786 and 1787, respectively. It was commissioned by their niece, Mary P. Carr. Ruth married the well-known John DeWolf when she was 52, and he passed away just three years later. Hannah married Captain Jabez Gibbs of Newport. Both families’ fortunes, explained Catherine Zipf, executive director of the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society, are inextricably and infamously linked to the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

However, Zipf’s research shows that the sisters’ relationship to that complicated legacy is anything but straightforward.

“In the same way that there are plenty of people who want to get out of the mafia and wish they weren’t born into it, there’s a lot of DeWolfs who wished the same thing about the slave trade,” she said. “They’re not a monolithic family, and everybody has a different reaction to their legacy.”

When Ruth DeWolf died in 1874, she bequeathed funds to build a church that would eventually become Trinity Episcopal Church in Bristol (Colt Andrews School now sits on that land, as the church was destroyed by the 1938 hurricane). The church was specifically ordered to not sell its pews. Raguin posits that this could indicate Ruth wanted the church to be open not just to those economically downtrodden, but also be racially inclusive.

The sisters also appear in records for donations given to the American Colonization Society, an organization equally fraught in terms of its stated mission — transporting freed slaves back to their ancestral African homeland, specifically to their own settlement, Liberia — and the actual harms and implications that mission wrought.

While there has been some disagreement over whether or not it can be said that the sisters were through and through “abolitionists”, Zipf is of the opinion that, at the time, the sisters probably thought such donations were for the betterment of humankind.

“Ruth and Hannah gave money but it doesn’t mean they were leading figures. It’s an organization you want to feel good about,” she said. “I’m sort of a believer that people don’t do something if they don’t think it’s a good idea.”

Regardless of what their intentions were, Dilworth said that he believed the window would have been an important symbol at the time it was installed.

“As a person of color, if I was living at that time and being subject to a lot of racism, a lot of hatred and everything else that goes along with being a person of color at that time, that any symbol such as this window would be seen as a major sign of hope,” he said. “As a place where one could feel protected and safe, perhaps.”

Helen Salisbury, a former Warren resident who experienced every different life event imaginable at St. Mark’s, from baptisms, to weddings, to funerals, said that indeed, the window was never something that seemed out of place.

“Never once do I recall any conversation about skin tone. It just wasn't a thing. It wasn't that people were refraining from discussing it. It just didn't come up,” she said. “It’s very much part of the Episcopal philosophy, and ideology. To be all encompassing and be inclusive…Everyone was welcome. Anyone and everyone was welcome in the church. So it was just, to us, a beautiful stained glass window.”

The lingering questions

Unfortunately, due to the sparsity of historical records surrounding the window, and the three women involved in its creation, many questions remain unanswered.

“Why this window in this place at this time?” Arnold wrote in an email. “What was the makers' intent? What actions or values or relationships was it commemorating? What was it affirming about the parish and the past, or what was it challenging the parish to going into the future? What was it saying to the town? Or the nation? What is it saying to us?”

“It's sort of like a bottle in the ocean with a note in it that says, ‘I was once here,’ and this is where the bottle has landed,” Dilworth said. “The people who sent the message are long gone, but the message is still a very curious one, and that makes you want to find out who these people were, and what their lives were about.”

For Raguin, it is not especially surprising to not have a “smoking gun” in the form of a historical record.

“You never get anybody telling you what they're doing,” she said. “We do not have King Louis IX, who built the Sainte-Chapelle, writing a cozy letter to his mom saying, ‘Gee mom, I'm so happy. I've got the Crown of Thorns and I've decided I'm going to do this.’ You don't have that.”

Raguin said that, through analyzing the original artwork the panels appeared to be based upon, and seeing the purposeful alterations the artist made in conveying them, she has little doubt that some kind of statement was being made.

“That was the absolute convincing moment that I said, ‘They really mean this,’” she said. “Whoever commissioned this window was saying something about these women, especially…it liberates me to have a great deal of confidence in, yes, they also wanted to say, ‘Jesus is our brother, and if you have black skin, Jesus, who is your brother, is going to have black skin and look like you.’”

For Dilworth, the questions regarding the merits of the window’s commissioning and its physical installation of is one he would love to know the answer to.

“This is a conversation that we would really love to hear. The conversation of how Mary Carr approached the parish and said, look, I have this idea to do a window, and guess what? Christ is gonna be a man of color. Would you be willing to install it? And somebody had to say yes,” he said. “It had to be this sort of very subtle political statement, you know, maybe quite outside of its religious context…I think in some ways, Mary Carr was saying this not just for herself, but perhaps even in some ways maybe speaking for the women of her time. And also for her aunts.”

Arnold is excited about the potential for future discoveries, and that people have already come forward interested in diving into newspaper archives and records to search for more pieces of the puzzle.

“The window is many different things for everyone,” said Emma Sheridan, a Warren native and project coordinator for Preserve RI who has volunteered to do more research. “For me, at this moment, it’s kind of a portal that we can step into and explore the complexity surrounding the window, and it’s meaning.”

The window’s future

Sheridan is not alone in her assessment regarding the window’s role as a conduit for continued conversation. Ultimately, that is Arnold’s primary goal when figuring out what to do with the window — to see it on display somewhere it can be viewed and discussed.

“I am absolutely committed to the window becoming a part of the public trust, so that all humans can see themselves in it. So people in Rhode Island and beyond Rhode Island can appreciate it for as long as a museum possibly can,” she said. “I think it will take a collaboration because it is a big object. And because there are unanswered questions, I would love to see university researchers, museum curators, educators and possibly the church itself re-entering the discussion — saying how do we make the most of this opportunity to share this artifact?”

For Zipf, the window is representative of the greater theme of mystery that surrounds the entire time period in which it was created — creating the perfect opportunity to dig in and search for answers.

“I think that this period of history as Americans is not super well understood…It has a lot of nuanced parts that involved a lot of conjecture about what people are doing and thinking. This window is something that breaks that history wide open,” she said. “I think we have much to learn and this window prompts us to do that.”