- FRIDAY, JULY 26, 2024

Empty seats hit an all-time high

New data shows that student ‘chronic absenteeism’ reached unprecedented levels last school year — which has a watchdog group reiterating that R.I.’s public education system is in crisis

Imagine society as a can of soda. The pandemic flipped that can down a flight of stairs and then popped the top.

Society has been fizzing, spitting and bubbling ever since.

The economy is …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

Empty seats hit an all-time high

New data shows that student ‘chronic absenteeism’ reached unprecedented levels last school year — which has a watchdog group reiterating that R.I.’s public education system is in crisis

Imagine society as a can of soda. The pandemic flipped that can down a flight of stairs and then popped the top.

Society has been fizzing, spitting and bubbling ever since.

The economy is out-of-whack, with price spikes, supply-chain anomalies and labor shortages now commonplace. The nation’s mental health crisis is documented with overwhelming evidence. The CDC recently reported that suicide rates are rising, especially among young people, who are feeling more hopelessness and despair than ever before.

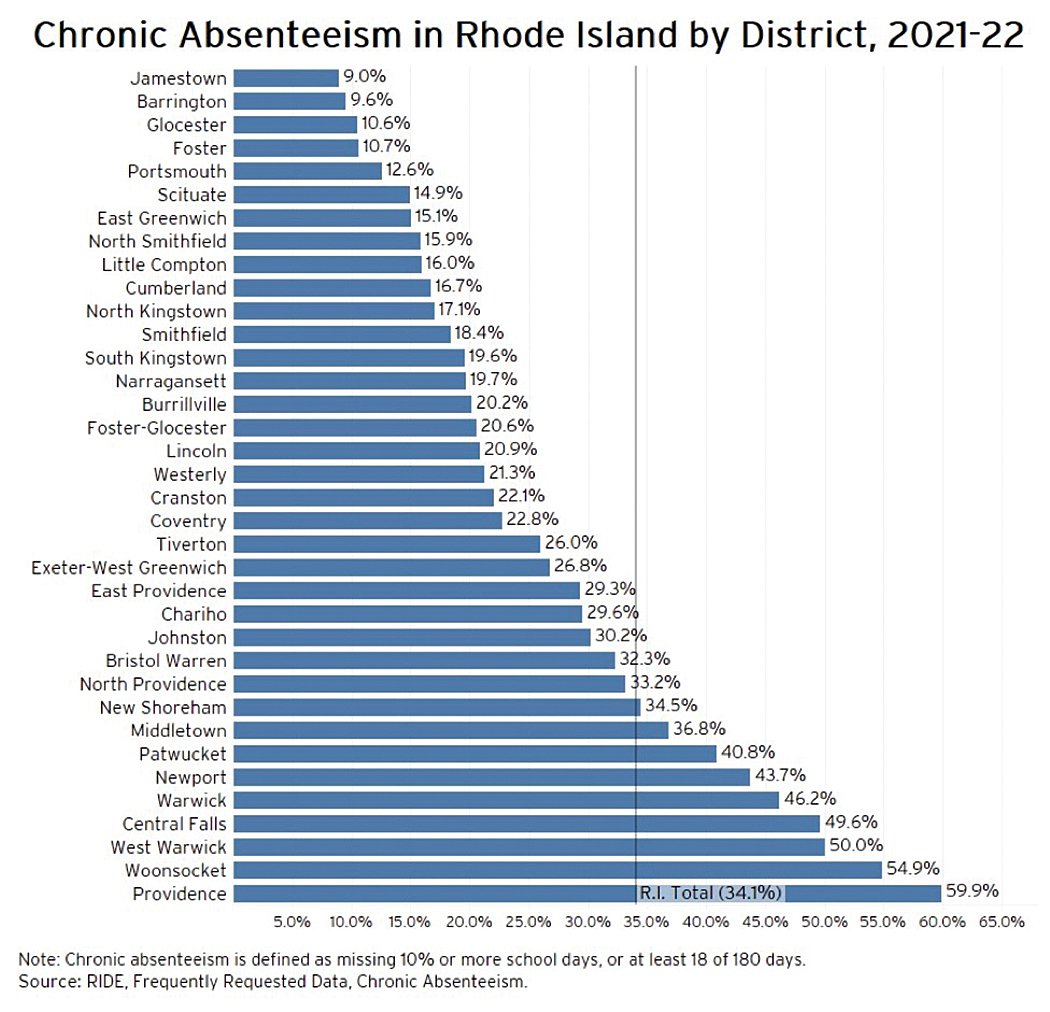

Now comes a sobering set of data from the Rhode Island Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the state’s public schools skyrocketed last school year. In 2021-22, one out of three students was “chronically absent” from school, meaning they did not come to school 10% or more of the time. In the standard, 180-day school year, they missed 18 days or more.

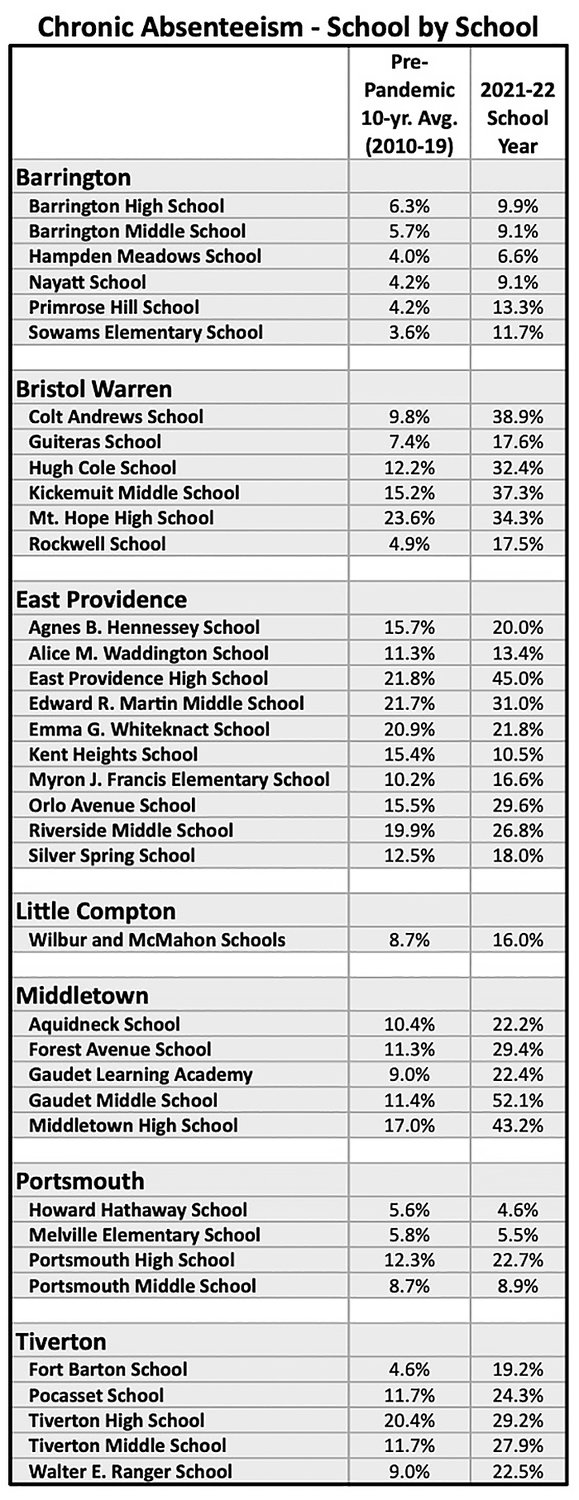

The numbers are crippling in some of the state’s most distressed communities, typically in the urban core. In Providence, 60% of students were chronically absent from school last year. Though the problems were exacerbated at the high school level, where 69% of Providence students were chronically absent, they were consistent across all grade levels. Even among students in Kindergarten to Grade 3 in Providence, 56% were chronically absent.

In Woonsocket, West Warwick and Central Falls, 50% or more of all students were chronically absent last school year. Locally, the Bristol Warren Regional School District experienced the highest levels of chronically absent students, at 32%. In East Providence, 29% were chronically absent. In Tiverton, 26% were chronically absent.

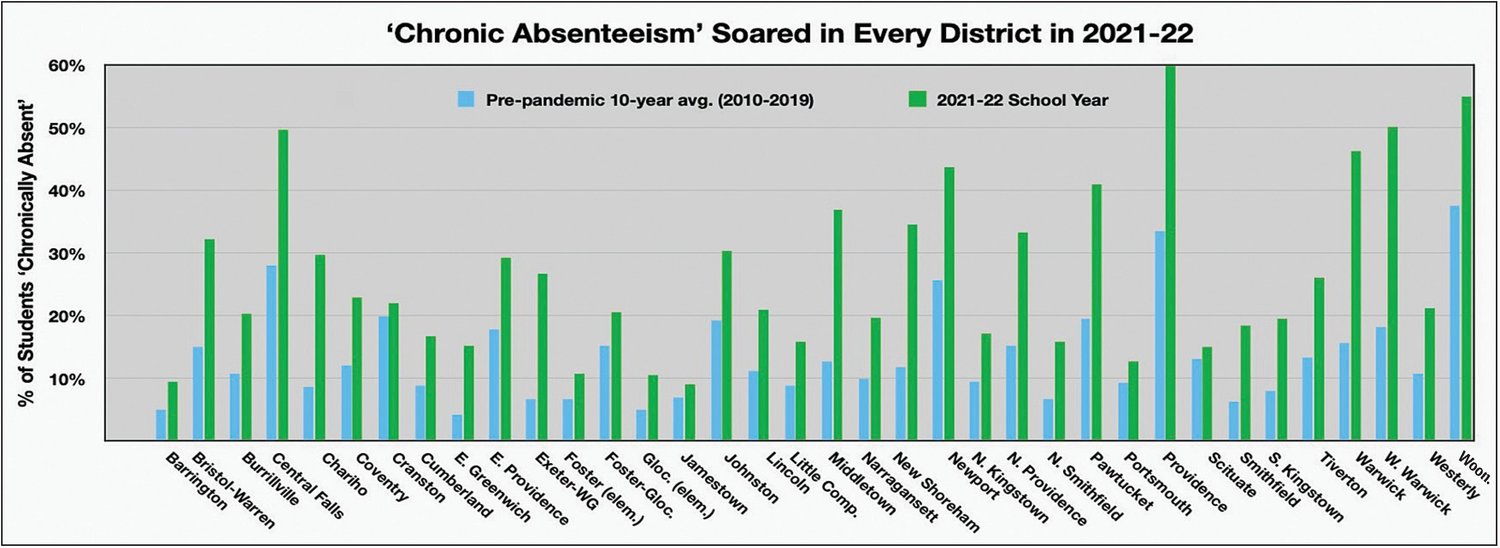

Even the state’s highest-performing districts — typically in the wealthier suburbs — were not immune. Though the suburban absenteeism levels are much lower than in the urban core, those districts still experienced record absenteeism last year.

In Barrington, 10% of students were chronically absent. It was the second-lowest rate in Rhode Island, but it was still double the district’s historical, pre-pandemic level. In East Greenwich, like Barrington a perennially top-performing district, chronic absenteeism reached more than 15% — tripling its historic, pre-pandemic average.

The data is consistent across all grade levels and all districts, and the message is clear: More students were absent from school more frequently than ever before.

Why are they missing school?

There are many possible explanations for the rise in chronic absenteeism, and the primary drivers may differ by community, but going back to the soda can analogy, the pandemic is the root cause of much fizzing and spitting.

Students who went through two years of closed, hybrid and disjointed schools are less engaged and more apathetic than ever before. Students suffering through their own mental health crises are less likely to care about or want to go to school. Student from disadvantaged families facing economic hardship are called to work more, to care for siblings more.

And then there are policies. Pandemic rules varied district to district, but some were universally common. Students who tested positive for the virus were sent home immediately, for a minimum of five, seven, sometimes 10 days. Some districts offered hybrid instruction, where students who logged in remotely were not counted as absent, but some did not. So a student who tested positive for Covid twice in a school year could be “chronically absent” through policy, not personal choice.

Even if they did not have the virus, many students were encouraged or required to stay home if they had symptoms of the virus, if they were sick in any way, or if they had head colds. So students who once would have come to school with the sniffles or a cough began staying home for days at a time. As the data shows, chronic absenteeism rose almost everywhere, with few exceptions.

A crisis in education

The “chronically absent” data for the 2021-22 school was released by RIDE just a few weeks ago, and it has so far brought more questions than answers.

One of the people devoted to understanding it better is Justine Oliva, manager of research with the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council (RIPEC). Oliva and her organization, a nonprofit nonpartisan group that has been a watchdog for government spending and administration for 90 years, has been sounding alarms about the state of the state’s public schools since last fall.

In October, RIPEC issued dire warnings that Rhode Island’s public education system is in crisis — and that was before the new chronic absenteeism data. When it released its report a few months ago, one in four Rhode Island students was chronically absent. Now that rate has increased to one in three, from 28% to 35%, in one year.

Oliva is working to get more data and more insights about absenteeism from RIDE. In the meantime, she warns that the bottom line is the bottom line. Interviewed last week, she said that regardless of the reasons why, “These students were not in their classrooms. These students were not learning. And this helps explain why we have such low student proficiency levels.”

RIPEC’s October report focused attention on a number of troubling signs beyond just the absenteeism. It warned that the Rhode Island education system was already in a state of crisis that worsened considerably during the pandemic.

“While Rhode Island ranks 12th highest for spending per student, its student outcomes are middling compared to the nation overall and low compared to other New England states,” said Oliva. “Equally as serious are the stark gaps between student outcomes across lines of geography, race and ethnicity, and other demographic features including poverty, disability status, and English language proficiency. The COVID-19 pandemic and the related closure of schools only exacerbated these issues.”

On the 2020-2021 Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System (RICAS), only one in three (33.2%) students in grades three through eight could demonstrate proficiency on the English Language Arts (ELA) portion of the exam, and only one in five (20.1%) students could demonstrate proficiency in math. On the SAT, fewer than one half (48.3%) of high school students were able to demonstrate proficiency in ELA and about a quarter (26.4%) could do so in math.

“That’s why we’re calling this an emergency. It’s a crisis,” said Oliva. “This needs to be treated like an urgent situation, and so far it has not been.”

Gaps across districts and demographics

RIPEC’s report goes into great detail about the achievements gaps across demographics. While it notes that Rhode Island is not alone in seeing students of color, students with special needs and students with limited English proficiency struggling in the classroom, it states: “The gap is notably wider in Rhode Island than in nation generally … Rhode Island posted the nation’s third-highest white/Hispanic proficiency gap for eighth-grade reading on the 2019 National Assessment for Education Progress. On the same assessment, proficiency rates for Rhode Island’s limited English proficient students were significantly lower than rates for these students in the U.S. overall.”

RIPEC goes on to warn that the performance gaps are even more troubling because nonwhite students comprise a larger percentage of students in Rhode Island than in other New England states, and that segment of students has grown dramatically in recent years, particularly Hispanic students. The percentage of students who are Hispanic nearly doubled (from 15% to 29%) in the past 20 years.

Lastly, RIPEC notes that demographics in the teaching ranks have changed little in that time. Thus predominantly white faculties are teaching to increasingly colored student bodies — “a factor shown to negatively affect student outcomes,” according to RIPEC.

What can be done about it?

The RIPEC reports goes further than just clanging the alarm bell. It offers seven recommendations for systemic change. It suggests the problems be addressed by all stakeholders, including government, parent, business and community leaders. It recommends more state funding for poorer districts, and for districts teaching “limited English proficient” students.

RIPEC believes the Commissioner of Education should be a Cabinet-level member of the governor’s administration, with more authority and influence over local districts. It also believes the state could do more to bolster teacher professional development; there should be greater efforts to recruit, retain and support new teachers, particularly in high-need areas and teachers of color; and policymakers should make room for more innovation and choice across school districts and within current and new charter schools.

An article in East Bay Life two weeks ago (“Students are leaving, but the money is not,” Feb. 8) revealed how public school enrollment has declined in nearly every Rhode Island school district over the past decade, but the population in public charter schools tripled over the same time period. Nonetheless, Oliva said, “In 2021, there were 5.4 unique applicants for every available charter school seat. So you still have a lot of families that try to get into charter schools, but can’t get in.”

RIPEC’s complete report on education is available here: https://ripec.org/2022-improving-ri-schools/

Other items that may interest you