A riveting account of an early pioneer for women’s rights

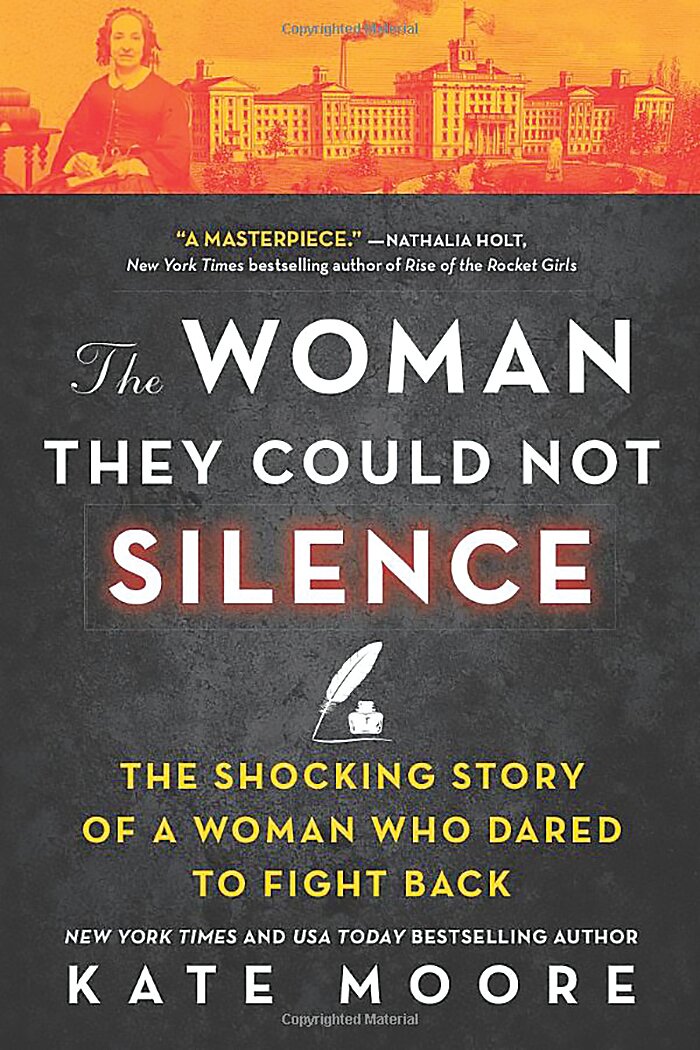

“The Woman They Could Not Silence”

By Kate Moore

In this riveting masterpiece of non-fiction, the author focuses on Elizabeth Packard, who in 1860, was declared insane by her …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

A riveting account of an early pioneer for women’s rights

“The Woman They Could Not Silence”

By Kate Moore

In this riveting masterpiece of non-fiction, the author focuses on Elizabeth Packard, who in 1860, was declared insane by her preacher husband, who committed her to an asylum for disagreeing with his religious views. In all else, she had been a model wife in the domestic realm, creating a comfortable, attractive home, preparing excellent meals, and caring for her six beloved children.

Throughout 21 years of marriage, she had followed her controlling husband’s dictates, but any demonstration of her own intellect angered him. Since he feared his congregation would be swayed by Elizabeth’s espousal of “new notions,” he had to silence her.

During that period, it was not required to prove a woman’s unstable mental condition. Reasons consisted of reading novels, for which her husband attempted to have the local library closed. Reading was considered a “pernicious habit” that put females in a “dreamy state” akin to insanity. Doctors believed another cause was the menstrual cycle, so mothers were encouraged to delay their daughters’ periods by cold baths and abstaining from meat and feather beds.

In addition, any woman who did not abide by the accepted roles society had defined for her was suspect. Another theory was the belief that mental instability sprang from the position of the uterus, for which substances were placed in the woman’s nose or vagina.

Other vices leading to female instability were “excessive talking, change of life, hard study, disappointed love, religious excitement, unusual zealousness, etc.”

In the asylum, Elizabeth met other “unsatisfactory” wives who had been admitted for simply “defying domestic control.” In her own case, Elizabeth declared she was there for “thinking her own thoughts.” Psychiatrists then had no formal training and relied entirely on the husband’s judgment.

She protested repeatedly: “In many cases it is not insanity, but individuality” that causes women to be committed. It isn’t fair to credit men’s lies and discredit women’s truths.”

The punishment for these protests was first isolation in a dark cubicle, and later imprisonment with the truly insane, where she existed among screaming, fighting, filthy women out of control, with tangled, wild hair, wading and wallowing in their own urine and excrement. This she declared was the “blackest night of her life.”

But even in this desolate, hopeless state, Elizabeth managed to take control. One by one she ministered to each inmate, washing their bodies and hair, combing out the tangles, washing their bed linens. Once she was rewarded with a blow to her eye that nearly cost her sight.

In addition to finding a purpose even here in a degrading institution, she began to keep records of the abuses she witnessed: the beatings, the straitjackets, the submersion in water that made the victim feel as if she were drowning.

After two years confinement, Elizabeth managed to send a letter to a liberal newspaper. Its publication secured her release. However, upon her return to her home and family, her husband imprisoned her in a locked bedroom, sealing the windows with boards, denying access to her children or friends.

Just as he was arranging to have her transferred to a different asylum, friends secured a trial at which the judge demanded her husband “prove” her insanity. Finally, a jury declared her of competent mind.

Still her problems continued: Mr. Packard had absconded with her own personal inheritance, as well as their children to a new location, leaving her homeless and penniless.

Read this “captivating and dramatic” story of one indomitable woman’s valiant fight for her identity and custody of her children in a misogynist world. Her success in publishing a book that revealed the injustice of the system against totally innocent wives led to a reversal of many laws.

A pioneer for women’s rights, she spent the rest of her life devoted to female empowerment against a patriarchal system that attempted to keep women in their place – subservient and powerless. In 1987, her contributions to society were recognized by the American Psychiatric Association.

Regarding the author, the book is based on extensive research, using trial transcripts, as well as Elizabeth’s original letters and memoirs. We owe her for so many advances; for example, until 1974 independent women were denied their own credit cards, nor could a single or divorced woman secure a loan without a male cosigning.

The reader will feel anger at the injustice to which Elizabeth Packard was subjected; admiration for her stalwart refusal to conform; and respect and gratitude to her for many of the rights we enjoy today – a truly remarkable woman portrayed by a very skilled author.

Donna Bruno is a prizewinning author and poet recently recognized with four awards by National League of American Pen Women.