- THURSDAY, APRIL 18, 2024

From the Middle East to Middle Road, Portsmouth

Tim Phelps broke the Anita Hill story and covered the war-torn Middle East before that. Now retired, he recently moved back to his childhood farm — but he’s not done writing.

PORTSMOUTH — For a journalist who introduced the world to Anita Hill, spent years as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East and covered the Supreme Court and Justice Department in …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Register to post eventsIf you'd like to post an event to our calendar, you can create a free account by clicking here. Note that free accounts do not have access to our subscriber-only content. |

Day pass subscribers

Are you a day pass subscriber who needs to log in? Click here to continue.

From the Middle East to Middle Road, Portsmouth

Tim Phelps broke the Anita Hill story and covered the war-torn Middle East before that. Now retired, he recently moved back to his childhood farm — but he’s not done writing.

Tim Phelps was born on one Portsmouth farm, then left another when he went off to cover the world as an ambitious, young reporter many years ago.

Now that he’s back, it’s only natural to ask him: How much has the town changed since then?

“You know, I have a reaction to this that surprises some people,” he said while sitting outside a house he now rents from the DeCastro family on farmland between Quonset View Farm and the Green Valley Country Club golf course on Middle Road. “I’m really amazed at how similar Portsmouth is to the town I grew up in. There’s a heck of a lot of development, but the character of the town, to me, is still the same. It still has a much different character from Newport.

“I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that the new construction of houses are done very tastefully — built in the old Colonial style. A lot of care has been taken to preserve the character of the town.”

His chat with a reporter was occasionally interrupted by the loud din of a tractor passing back and forth on land sloping down toward Narragansett Bay. The panoramic view includes the south end of Prudence Island, which his great-grandfather Charles Hunter used to own and is now managed by the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

“They just picked rows of string beans,” he said. “Already, they’re plowing the plants under and they’ll plant something else.”

Mr. Phelps was born in 1947 on a 40-acre farm on Glen Road, where The Pennfield School now stands.

“My father (Walter Kane Phelps) needed more land, so when I was 5 he bought this property and we moved over here. This is 90 acres,” he said.

Walter Phelps, who died in 1969, was a former longtime chairman of the Portsmouth School Committee, and crusaded to get the high school built. (“In those days, he used to hire the teachers himself,” said Mr. Phelps.)

He has fond memories of his childhood years on the farm, and delighted in pointing out different buildings and their stories. “That house was originally the slaughterhouse for the chickens,” he said, pointing to his right.

And here’s some quirky Portsmouth trivia: One of the farmhouses was home to a boy who’d later go on to direct a Netflix movie which might ring a bell: “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.” Eric Goode, a lifelong conservationist and animal lover, was born in Portsmouth during a raging blizzard in late 1957.

“He was born in mid- to late-December and there was an early snowstorm,” said Mr. Phelps, who would have been 10 at the time. “The driveway and Middle Road were blocked. My father had to hitch up the farm wagon to the tractor and take him out to Union Street, across the fields, to be born.”

Mr. Goode’s stay in Portsmouth was brief, as he was raised mostly in New York before relocating with his family to California when he was 8.

Descended from settlers

Mr. Phelps has traced his ancestry back to some of the original settlers of Portsmouth and Newport, and said he’s a direct descendent of Philip Sherman, one of the signers of the Portsmouth Compact in 1638.

Rebecca Cornell, who was “killed strangely” in 1672 in her home where the Valley Inn Restaurant now stands — her son Thomas was hanged for the crime after a trial that relied on “spectral” testimony —was his “great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother,” Mr. Phelps said. (He spent his elementary school years at the former Coggeshall School, where the Portsmouth Community Theater debuted a play about the Cornell trial several years ago.)

He sold the Middle Road farm to Steve DeCastro 20 years ago. “Five years before that, my brother Michael and I preserved the farm through the Nature Conservancy and State of Rhode Island. No development; this will always be a farm,” he said.

Now a renter on land where he grew up, Mr. Phelps said the DeCastros “are doing a marvelous job” in caring for the land. “In fact, it’s in better shape now than when I owned it.”

— Jim McGaw

PORTSMOUTH — For a journalist who introduced the world to Anita Hill, spent years as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East and covered the Supreme Court and Justice Department in Washington, D.C., Tim Phelps’ newspaper career got off to a rather unassuming start.

“I got interested in journalism when I was in college — actually, through the Newport Jazz Festival,” said the 73-year-old Mr. Phelps, speaking from the 90-acre Middle Road farm where he lived as a child — and now as a retiree. (See story at left.)

“I wrote a letter to the editor (to the Providence Journal) complaining about a review, and I was so impressed with seeing my name in print, I started to wonder. Within a year, I was covering the festivals for the Journal, as a kid.”

That was 1968, when Mr. Phelps was just 21. He had sat in the audience when Bob Dylan made his Newport Folk Festival debut in 1963 and when the singer scandalized the folk scene by going electric in 1965. Now he was hobnobbing with the likes of Charles Mingus and Mississippi John Hurt backstage, writing about his musical heroes as a summer intern.

“I was hooked immediately,” he said.

After he got out of college the following year, the Journal hired him back. Covering music festivals wasn’t his only beat. “I remember when I was a kid as an intern in the Newport bureau, taking a picture of then-Gov. John Chafee with this old Rolleiflex,” he recalled. “Chafee yelled at me: ‘Don’t you know you’re not supposed to take a picture of me with a drink in my hand?’”

Vietnam cut short his time at the newspaper, however, and he enlisted in the Army in the fall of 1969. “I only worked there a total of maybe nine months, but it was such a good paper. It was formative in terms of journalism skills. You really learned how to be a thorough, tough reporter. In those days it was the best paper in New England by far,” he said.

But better things were ahead, and a wise decision early on set the stage for his future success as a reporter.

“I heard about the Army language school and I went up to Providence to talk to the wire editor, who put the foreign and national news in the paper,” Mr. Phelps said. “He was a wise old guy, and I asked him what would be a good language to study for a reporter who wanted to be a foreign correspondent. He suggested Arabic. This was before the oil embargo, before the terrorism and what not. It was really smart advice. It really shaped my career, because I later spent seven years as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East.”

He studied Arabic for a year at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, Calif. After his Army stint he got a job at another formidable newspaper, The St. Petersburg Times (now The Tampa Bay Times), but he grew bored and was itching to get to the Middle East.

Cairo and the NYT

“In 1976, I quit my job and moved to Cairo. I ended up working as a full-time stringer for the New York Times,” said Mr. Phelps, who still marvels at the fact he was getting bylines in the national newspaper of record “as a young kid in his 20s.”

He worked for the Times for two years in Cairo, and then was hired by The Baltimore Sun, first as the federal court reporter, and then the statehouse bureau chief. His favorite job at the Sun was one he created himself, however.

“I got tired of the daily grind. I created a new job and appointed myself as the Charles Kuralt of Maryland, roving around the state, looking for news and features. I really enjoyed that.”

But the Middle East came calling again. In 1985, New York Newsday hired him to open up a bureau in Cairo, where he spent the next five years.

“I covered every war and revolution and whatnot,” Mr. Phelps said. “I did a lot of what I thought were interesting stories about what was going on in the countryside. Most reporters didn’t have the time to travel in Egypt, but because I was there full-time, I could get around. I was almost the only reporter who knew Arabic. Not that I was fluent, but it really created a path to doing good journalism.”

He lived in the West Bank, and his first story was about the food riots in Egypt in January 1986.

“The next month, the U.S. bombed Libya; I was in Tripoli for that,” he said. “I thought, ‘Phelps, you didn’t give a lot of thought to what you were getting yourself into, did you?’ I thought about this farm, and how much I wished I was back here instead of being in Libya being bombed by the Americans.”

Mr. Phelps, who’s been married twice and has two adult children, left behind a 6-year-old daughter when he first went to the Middle East. “That was hard,” he said. “You would get to come home once a year in the summertime.”

Mr. Phelps had originally planned to return home to his family in 1990, but Saddam Hussein had other plans. “I was actually packing to come home, and then Saddam invaded Kuwait. Much to my daughter’s consternation, I ended up there another year. I was in Iraq and Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, all of those places. That was pretty intense.”

Hazardous job

Covering the Middle East could be dangerous work. Mr. Phelps usually worked on his own, with no bodyguards. “You just have to look out for yourself,” he said. “Different correspondents have different levels of danger they can tolerate. I tried to be relatively careful. One of my best friends in the Middle East, Marie Colvin, was killed in Syria.”

Ms. Colvin, a foreign affairs correspondent for the British newspaper The Sunday Times, was killed while covering the siege of Homs in February 2012, after crossing into Syria on the back of a motorcycle.

“She went into a city that was being bombarded,” Mr. Phelps said. “That’s a risk I wouldn’t take. But it’s certainly not safe by most people’s standards when you’re in the middle of a war zone. I was in Bagdad when it was being bombed by the Iranians, and I was in Iran when it was being bombed by the Iraqis. I didn’t particularly like it, but correspondents got hooked on it. I think you get a rush from surviving a very dangerous situation, but I didn’t become dependent on that rush like some of my friends did.”

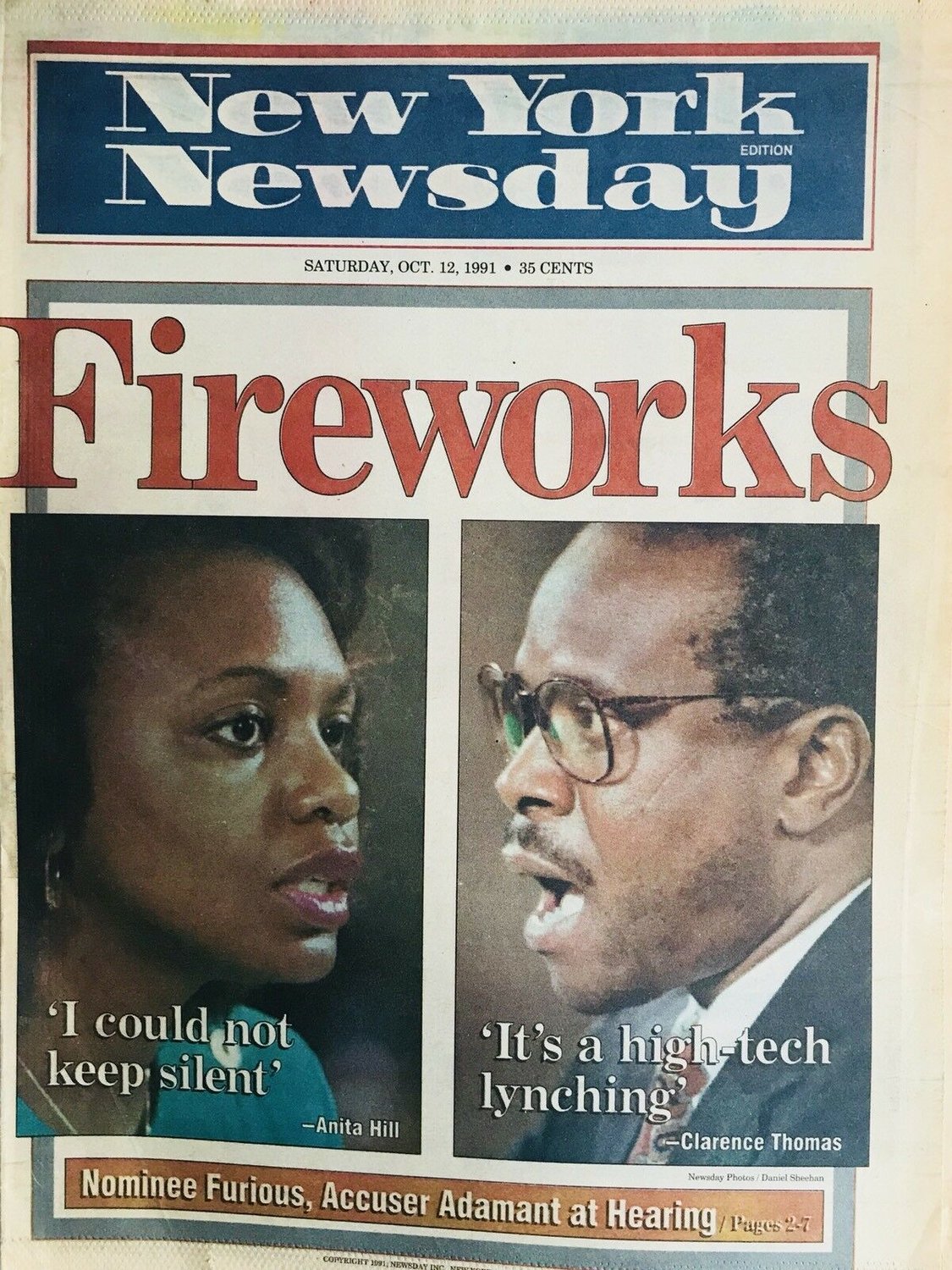

Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas

Mr. Phelps finally returned to the states in 1991, looking forward to a rest from years of covering war zones far from home.

“And then I ended up getting involved in a whole other kind of war in Washington,” he said.

Newsday assigned him to cover the U.S. Supreme Court, which had fascinated him since his days of studying constitutional law as an undergraduate.

“The first story I covered was Thurgood Marshall’s resignation (June 1991),” he said. “I knew Thurgood Marshall; through family and friends I had gotten to know him a little bit, so I took a particular interest in that vacancy. So, when Clarence Thomas was nominated, the conventional wisdom in Washington was that because he was an African-American, there’s no way the Democrats could oppose him. So, not everybody examined that nomination with the same fine-toothed comb that they might have. But as a local reporter, I just did what I would do on any nomination, and started digging into his past.

“Fairly quickly, the name Anita Hill came up.”

Ms. Hill’s claim — that Judge Thomas had sexually harassed her as her supervisor at the Department of Education and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission — gave Mr. Phelps the biggest scoop of his career. At the time, however, he wasn’t sure what he had.

“I find that in the newspaper business, you never quite know how much impact a story’s going to have,” he said. “Some really big stories seem to pass over with hardly a whimper, but they tore up the front page and put it on the cover. An editor at the paper insisted that I fly out overnight to Oklahoma to try an interview her. I really didn’t know how big a story it was going to be, and then when I got to Norman, Oklahoma, where she was a law professor, the following morning there were TV trucks lined up all up and down the street at the law school. I realized that this story had a huge impact.”

His reporting and Ms. Hill’s testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee during Judge Thomas’s nomination hearings created a watershed moment — the first time a national spotlight had been aimed at workplace sexual harassment.

“Part of the problem was that people — men — hadn’t heard of sexual harassment. That thought this was just some bogus, new, flaky thing the Democrats had come up with,” he said.

Ms. Hill’s graphic and damning testimony galvanized the country, but didn’t sink the nomination. Judge Thomas was confirmed, and Ms. Hill was demonized by many people who doubted her story.

“Objectively, one can say she clearly didn’t get a fair shake. It was handled horribly by this Senate Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by the presumptive Democratic nominee for the presidency this year (Joe Biden). They just did an awful job. The Republicans attacked her full on, and the Democrats did a terrible job of protecting her from that,” Mr. Phelps said.

Ms. Hill’s story did end up making a difference, however. After the hearings, Congress passed a law giving harassment victims the right to seek federal damage awards, back pay, and reinstatement, and private companies started training programs in hopes of deterring sexual harassment. Today, Anita Hill is considered a pioneer of the #MeToo movement.

If the hearings were held today, Mr. Phelps said he’s confident the outcome would be completely different. “The fact that sexual harassment is not only an accepted fact but it’s sort of one of the issues at the moment, I think Clarence Thomas wouldn’t have stood a chance in today’s atmosphere.”

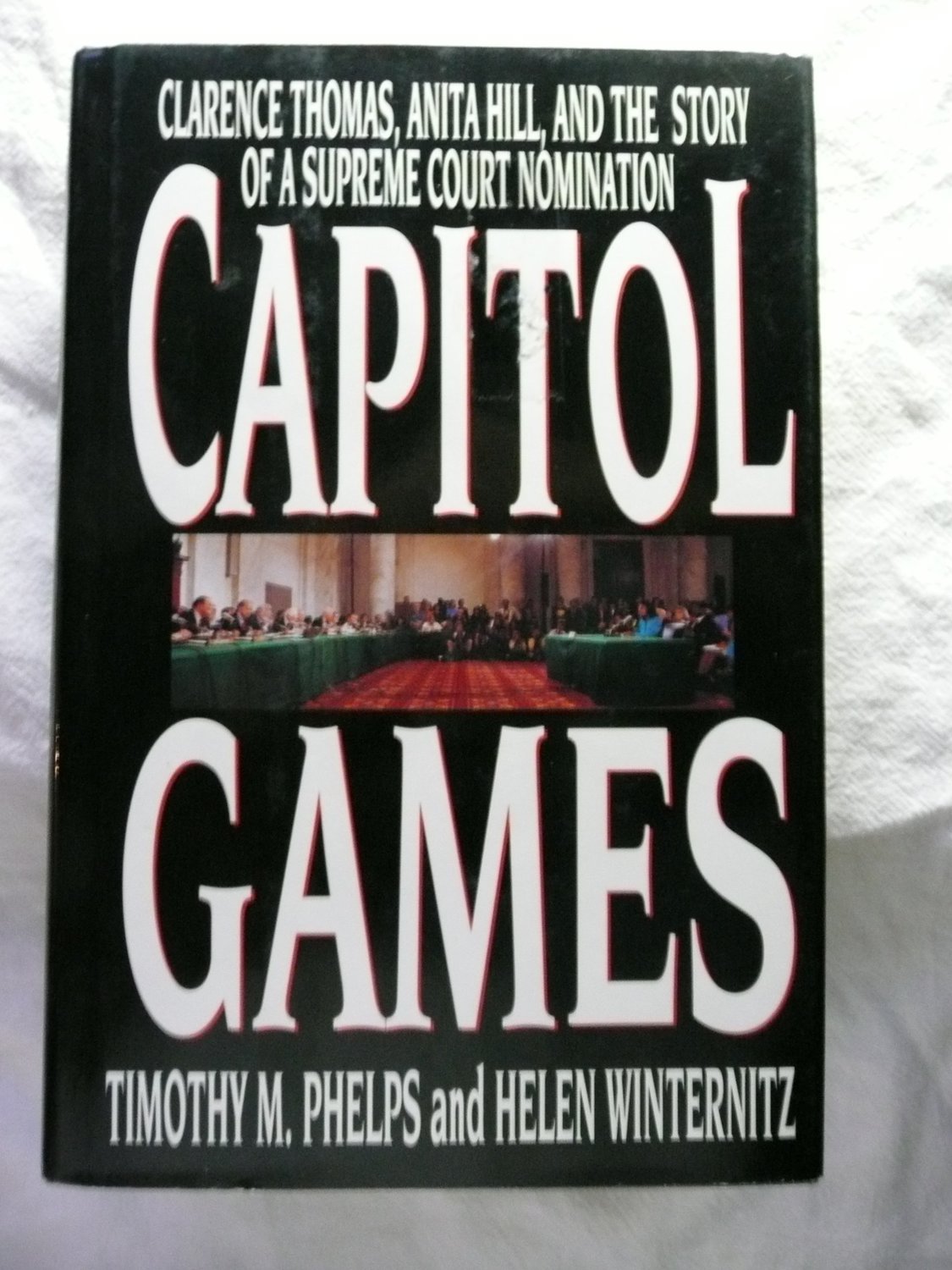

Mr. Phelps co-authored a book, “Capitol Games: Clarence Thomas, Anita Hill, and the Story of a Supreme Court Nomination,” which was published in 1992. It was later turned into “Confirmation,” a docudrama by HBO, which had hired Mr. Phelps as a consultant.

“I got a little taste of Hollywood that way, and they did an excellent job.”

He’s run across Ms. Hill several times since then.

“A few years ago, I wrote a story about her when the first documentary about her came out,” he said. “I called her up, not knowing how I would be received, because she hadn’t wanted to go public. It was me who outed her, and I felt some guilt about that over the years. I told her I was sorry, and she was very nice. She basically said her life changed for the better, eventually.”

Los Angeles and retirement

Mr. Phelps spent the last eight years of his career as an editor and reporter for the Los Angeles Times, a sister paper of Newsday. In all, he worked for eight newspapers — three of them twice. He’s particular proud of working two different stints at The Baltimore Sun.

“The Sun said I was only the second reporter who had the temerity to leave that they’d ever hired back.”

He retired on Jan. 1, 2016. Looking back, he said it was the perfect time to pack it in. “I got out just in time. I wouldn’t have wanted to be there for what’s going on now,” said Mr. Phelps, who ended his career covering the Justice Department. “I just would have found it difficult to be objective about what’s going on right now.”

Current project

Now his own boss, Mr. Phelps is working on a book about slavery on Aquidneck Island and his ancestors’ close connection to it.

“I was shocked to learn about 10 years ago that Newport was not only a commercial center for the slave trade, it was the center for the slave trade. We didn’t hear about it in school, it wasn’t discussed at home. My father is descended from many of the names in Newport.”

The book project is what lured him back to Portsmouth. Two winters ago Mr. Phelps was here doing research and stopped to see the DeCastro family, which bought the farm from him 20 years ago.

“They said, ‘We have a house for rent if you’d be interested.’ When I sold the farm 20 years ago, I tried to put in a clause saying I could come back and rent. It was kind of an agonizing decision because I had built up such a life and so many friends in Washington. And so last year I came up for the summer, and loved it. And then I sublet this house for the winter, and went back to Washington. In May, I moved here and decided to make this my primary residence.”

Mr. Phelps, who lives in one of the farmhouses by himself, still plans on wintering in Washington, where most of his friends are. He’s “about to press a button” on a proposal for his slavery book, but he has no set timeline on when it will be done. That’s the luxury he has now.

“I had always thought I would die with my boots on in the newsroom,” he said. “I never had any ambition to retire, but I was surprised to find how great it was to not have a deadline every day and to be my own boss to do what the heck I want and to write what I want.”

Please support your local news coverage

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the local economy - and many of the advertisers who support our work - to a near standstill. During this unprecedented challenge, we continue to make our coronavirus coverage free to everyone at eastbayri.com - we believe it is our mission is to deliver vital information to our communities. If you believe local news is essential, especially during this crisis, please consider a tax-deductible donation.

Thank you for your support!

Matt Hayes, Portsmouth Times Publisher

Other items that may interest you