- TUESDAY, APRIL 23, 2024

In Portsmouth: Learning to spot the warning signs

Every Student Initiative trains middle-schoolers in suicide prevention for the first time

PORTSMOUTH — Abby, a 13-year-old eighth-grader, is one of the most popular girls at middle school. She has a crush on a boy, but since he’s one of the most popular and best-looking boys in school, she doesn’t know if he thinks she even exists.

One day the boy adds her on Snapchat and they spend a month getting to know each other, although they never spend time together in person. Her crush tells her she’s special, and maybe they should date. Abby’s excited, but he asks her not to say anything to anyone just yet.

They continue this way for another month, and Abby suggests they spend some time together. He says sure — but first she must send him pictures of her body so he knows it’s real. Abby doesn’t like the idea, but she reluctantly agrees.

The next day the boy doesn’t answer any of her Snaps, and by night the entire grade learns that Abby sent pictures to the boy, who was circulating them around. Her friends are angry with her; Abby tries to explain, but no one believes her.

Students start saying mean things about Abby, who is now eating lunch in the bathroom and won’t talk to anyone in school. Her parents notice the change in her behavior, but when they ask about it Abby storms away and slams her door. Her dad blames her behavior on “hormone changes.”

After her parents go to sleep, Abby sneaks around the house and takes two bottles of her parents’ alcohol, drinking all of it. Then she begins to search the house for any pills she can find, in an attempt to end her life.

That’s a true story, although Abby is not the girl’s real name. Steven Peterson, executive director of Be Great for Nate (BG4N) and a licensed clinical social worker, said “Abby” was a girl he worked with years ago in another school district. The noise she made while stumbling around the house looking for pills woke her parents, who got her help. She’s doing fine these days, Mr. Peterson said.

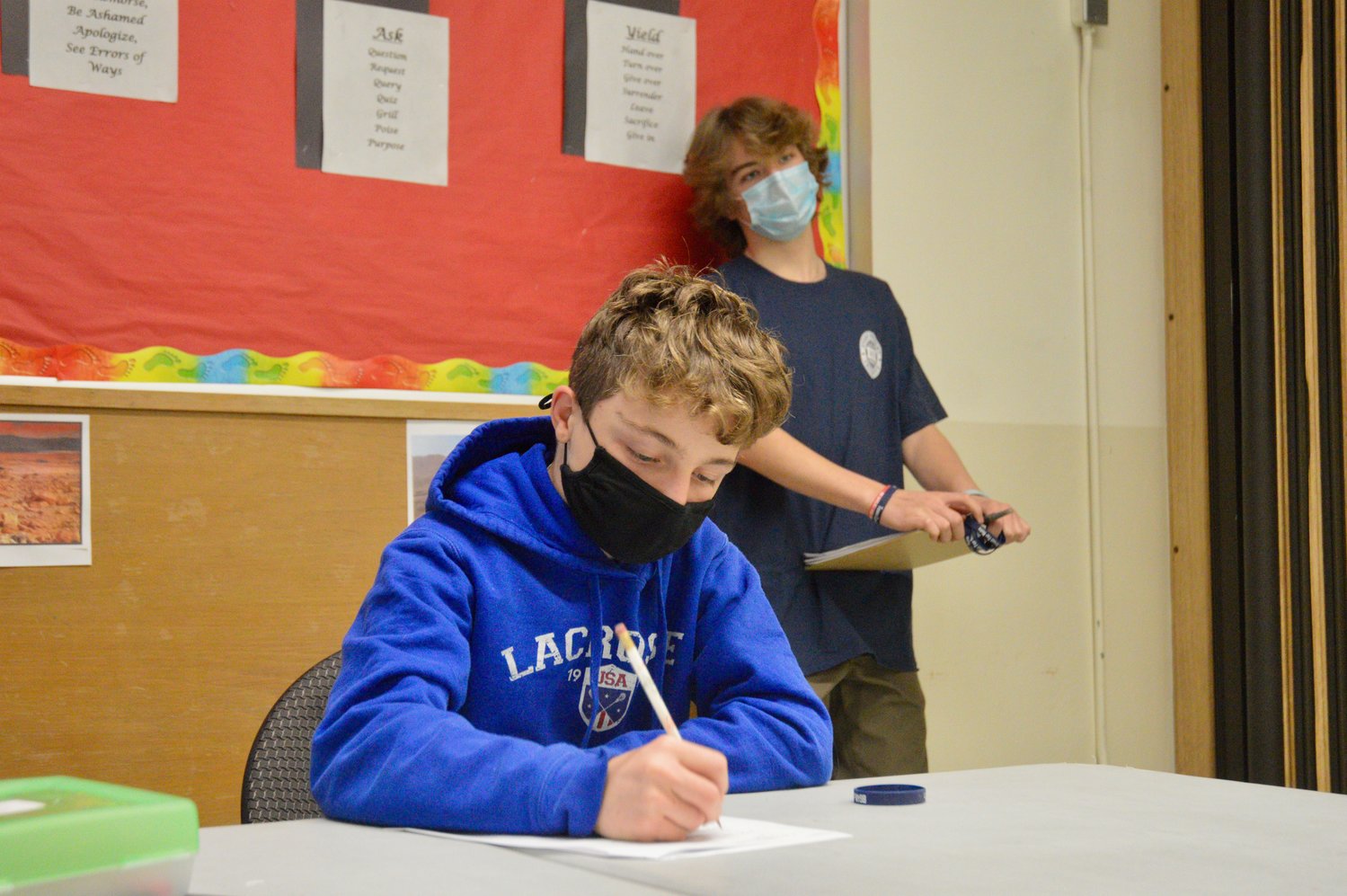

Abby’s story was just one of several true scenarios presented to about 90 middle school students during a suicide prevention training program conducted by Every Student Initiative (ESI) at St. Barnabas Church Sunday night, March 14.

ESI, which falls under the umbrella of the nonprofit BG4N. advocates for more mental health resources for students in public schools. Formed in the wake of the February 2018 death by suicide of 15-year-old Nathan Bruno, a student at Portsmouth High School, ESI has traditionally been made up of high school-age students who either live in or attend school in Portsmouth. But now the organization is reaching out to middle schoolers, who are eligible to receive not only training in suicide prevention, but also membership into ESI.

“This is our first time giving it to kids in the middle school,” Mr. Peterson told students who registered for the training. The week before, some of their parents (parishioners at St. Barnabas) and teachers received the same training. It’s the only suicide prevention training of its kind in the United States, he said.

“We’ve given this training to over 100 kids … plus last week, 40 adults. This is the biggest group we’ve even given it to. I’m giving this training today, but eventually ESI kids will be doing this,” said Mr. Peterson, noting the high schoolers still need 20 hours of training before they can take the ball and run with it on their own.

A few ESI students spoke to both the middle school students and adults and assisted with the evaluations — all participants were given a pre-test and a post-test to see how much knowledge they had gained. According to Mr. Peterson, there is nearly a “300 percent” increase in participants’ suicide prevention skills immediately following the training.

Hailey Pratt, a PHS senior and the current president of ESI, said she learned a lot about spotting the warning signs in troubled classmates and others after receiving the training.

“After you get this training, you’re really more aware of the people around you. You don’t judge people just for the way they’re acting,” she said.

The statistics on suicide are sobering: In 2018, 4,600 young lives were lost to suicide in the U.S., and that number is expected to increase with COVID-19 isolating people more. There are more than 3,000 suicide attempts by American teens daily.

“In one month you could fill Gillette Stadium with all the high-schoolers who attempted suicide,” said Mr. Peterson, noting it’s the second leading cause of death for youth in the U.S., with accidental death being the first.

Risk factors

During the training, participants were taught some of the risk factors of teen suicide. The biggest one is a previous suicide attempt. “If you’ve previously attempted suicide, you’re more than 300 percent more likely to attempt it again,” said Mr. Peterson.

Mental health disorder is another risk factor, but it certainly doesn’t apply to everyone who attempts suicide. “If you know enough about Nathan’s situation, you know he had no mental illnesses,” Mr. Peterson said.

Other risk factors include a relationship loss — a big reason for teens; substance abuse; history of abuse or mistreatment; financial or social loss; easy access to methods (“We have three bridges on this island that are readily available,” he said); transitions such as divorce, moving to a new location or changing schools; bullying, including cyberbullying (“Bullying used to happen at school and then it was over. Now it’s 24/7.”); and a recent traumatic or stressful event. Those who identify as LGBTQ+ or Native American are also significantly more at risk.

What are the signs?

ESI also went over the signs that someone may take their life — shifts from their normal behavior.

These include a preoccupation with death at inappropriate times; talking about feelings of hopelessness; talking about being a burden to others (“Life would be so much easier if you didn’t have to deal with me.”); a decline in academic or athletic performance; increase in recklessness or risk-taking; isolating or withdrawing; neglecting personal hygiene and appearance; and more.

Immediate red flags

Among the immediate red flags, which indicate a person will attempt suicide within 48 hours: The person says he wants to kill himself, gives away prized possessions, writes a suicide note, or shows extended uncharacteristic mood or personality swings followed by extreme happiness (or mania).

Another red flag may surprise some: They clean their room. “In some cases, they already feel they have been such a burden to their family, they don’t want to leave a messy room for them as well,” said Mr. Peterson.

What to do?

So what do you do when you recognize the warning signs? The first thing is to talk to the person to see what’s troubling them. Be straightforward and ask whether they intend to kill themself. “It will never cause a suicide, but it can prevent one,” said Mr. Stevenson.

If the answer is yes, do not leave them alone, and contact a trusted adult, such as a parent, school social emotional support staff member, a social worker, psychologist or therapist. Older students, in high school, are trained how to ask police to conduct a wellness check on someone who may be at risk of suicide.

Each table of students was then given a scenario — similar to Abby’s — about a student who may be at risk of suicide. They were instructed to work together in coming up with the risk factors, signs, red flags and course of action — including the earliest time to intervene.

Abby wasn’t the youngest child they heard about. That would be “Isaac,” a 5-year-old kindergartner from another town who witnessed his father beating his mom so badly she had to be hospitalized. His father, with whom he had a good relationship, was arrested and incarcerated.

Isaac started acting out in school, hitting classmates when things didn’t go his way. He played violent video games and watched violent YouTube videos at an older neighbor’s house, and told his teacher he was going to stab her in the neck with his pencil until she was dead. His drawings and writings were preoccupied with death, and he told his teacher he wanted to die.

One day Isaac’s mom looked under his pillow and found several steak knives. “Isaac planned on killing himself that night — at 5 years old,” said Mr. Peterson, who called Isaac his “little buddy.” The boy is now in middle school and is doing well, he said.

Stan’s story

Another scenario was about “Stan,” a 17-year-old high school junior whose athletic career came to an abrupt end due to a concussion. One top of that his home caught fire; no one was injured but many belongings were destroyed. Stan lived in several different homes before the family house was rebuilt.

He also burst his appendix, and returned from the hospital high on pain pills. Stan constantly told his friends what a burden he was to everybody and wrote a note, detailing where all his stuff should go.

Mr. Peterson then revealed that he was “Stan.”

“This is my story from when I was in high school. I attempted to kill myself three times in one year,” he said.

The 100-plus high school members of ESI know Mr. Peterson’s story well; it illustrates how certain circumstances can put anyone at risk of suicide. If any of the middle school students at St. Barnabas on March 14 want to learn more about his story of recovery, they’d have to join ESI themselves, he said.

“That’s my cliffhanger.”

For more information about Every Student Initiative, visit bg4n.org/esi.

Other items that may interest you